Archaeologists have uncovered ancient stone tools on the Isle of Skye that shed new light on Scotland’s oldest known human inhabitants. Dated to 11,500 to 11,000 years ago, the tools come from the Late Upper Palaeolithic (LUP) and show early humans ventured far further north than previously believed.

The discovery, led by University of Glasgow Professor Karen Hardy and local archaeologist Martin Wildgoose, is the largest concentration of proof of the early presence of people along Scotland’s west coast. The study was published in The Journal of Quaternary Science in a paper titled At the far end of everything: A likely Ahrensburgian presence in the far north of the Isle of Skye, Scotland.

The research team from Leeds, Sheffield, Leeds Beckett, and Flinders University in Australia collaborated to reconstruct the ancient sea levels and landscape of the region.

It was during the LUP period that western Scotland was largely recovering from the Younger Dryas (or Loch Lomond Stadial), a period when the landscape was glaciated. Nomadic hunter-gatherer tribes of likely northern European Ahrensburgian culture are believed to have traveled across the challenging journey through Doggerland, which is now submerged under the North Sea, to reach Britain and eventually the Isle of Skye.

Professor Hardy called this migration “the ultimate adventure story,” explaining, “As they journeyed northwards, most likely following animal herds, they eventually reached Scotland, where the western landscape was dramatically changing as glaciers melted and the land rebounded as it recovered from the weight of the ice.” She pointed to Glen Roy’s famous Parallel Roads as evidence of the dramatic transformations in geology these early inhabitants would have witnessed.

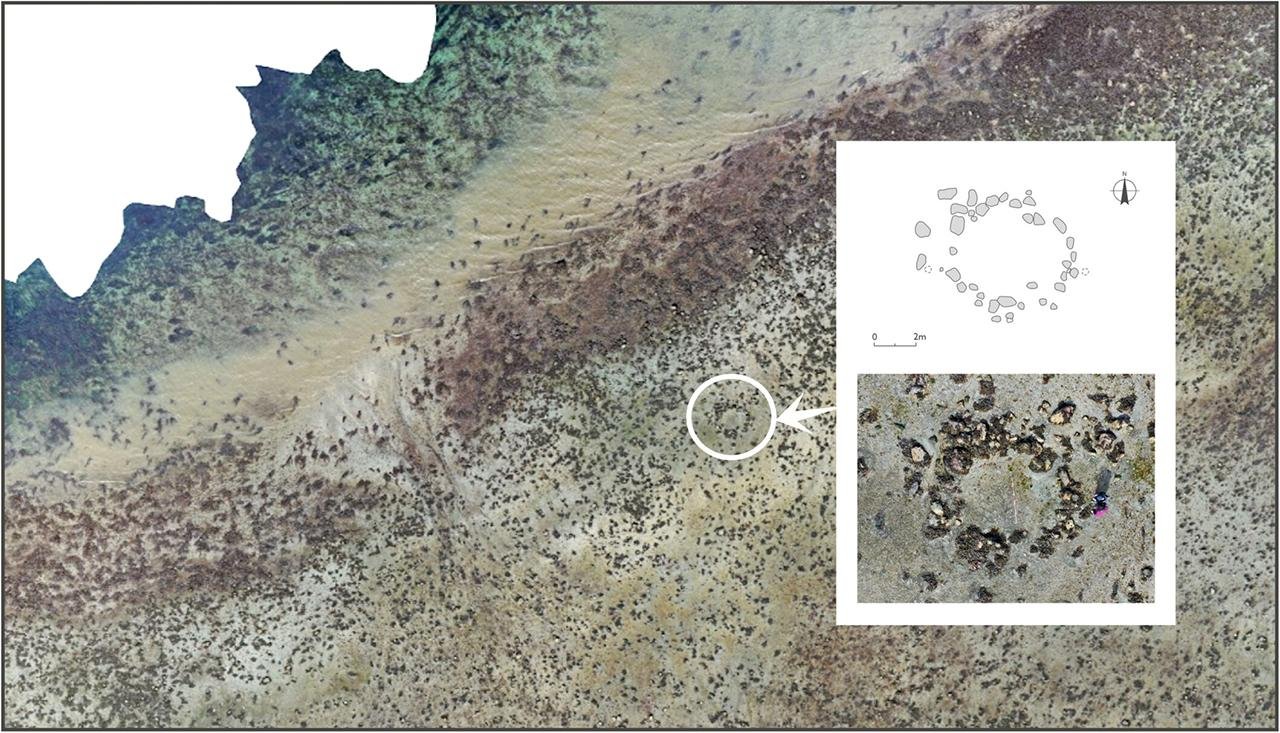

When they came to Skye, the group skillfully used locally sourced stone to produce tools and wisely settled near coastal and riverine resources. They also valued natural resources such as ochre, which was greatly valued by ancient people.

While direct evidence is sparse—areas like those on Skye have been found largely by chance—the article argues that the pattern of Ahrensburgian finds over areas like Tiree, Orkney, and Islay indicates a larger population than previously assumed. While the original sites are now inaccessible, the ancient environment may still be imagined around sites like Sconser, where lower sea levels once connected islands like Raasay to Skye.

Comments 0