A recent discovery from the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography at the University of Turin introduced new data on South American tattooing practices during ancient times.

A team of researchers has identified facial and wrist tattoos on an 800-year-old female mummy, with patterns never before seen in the archaeological record. The findings were published recently in the Journal of Cultural Heritage.

The mummy, whose remains were donated to the Italian museum nearly a century ago with little contextual history, is believed to be Andean. Although cultural affiliation and provenance are unknown, the woman’s burial posture—in an upright flexed position wrapped in layers of textile—suggests that she was buried in a traditional Andean funerary bundle known as a fardo. Radiocarbon dating of the clothing adhered to her body places her between 1215 and 1382 CE.

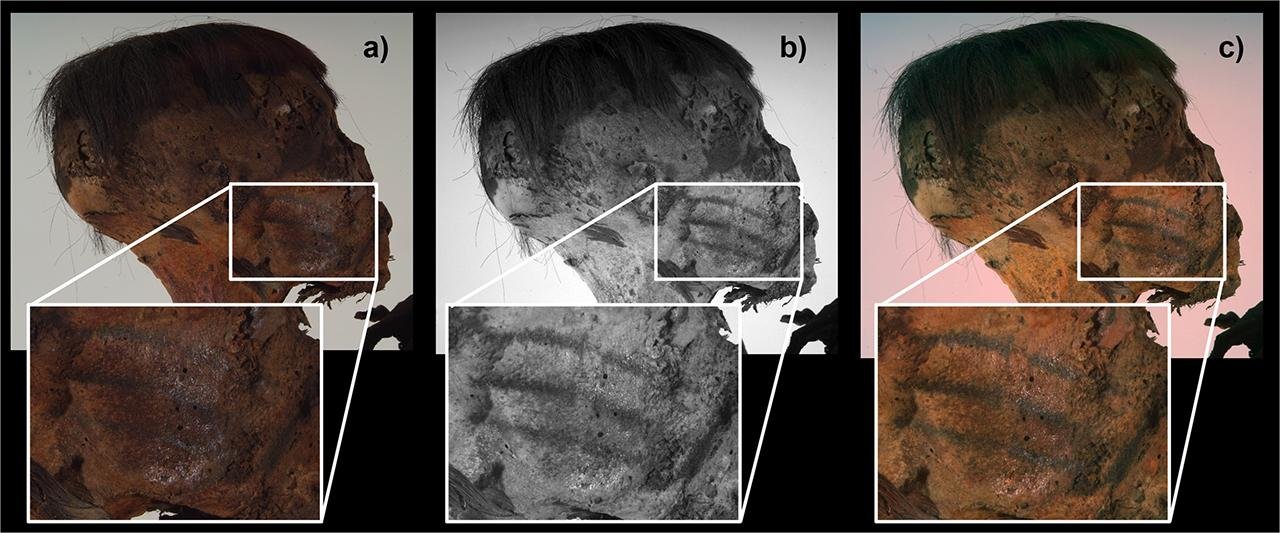

What is most notable about this mummy are the tattoos discovered with the help of advanced imaging techniques. While a few could be seen with the naked eye, researchers used 500–950 nm infrared false-color imaging and 950 nm wide-band infrared reflectography to make the hidden ink patterns visible. With these methods, three straight lines running from the woman’s mouth to her ear on each cheek and an S-pattern on her wrist were revealed.

Facial tattoos were rare in Andean cultures, and cheek markings are even rarer. “The three detected lines of tattooing are relatively unique: in general, skin marks on the face are rare among the groups of the ancient Andean region and even rarer on the cheeks,” the researchers wrote in their study. The wrist tattoo, though located in a traditionally tattooed position, is described as unusually simple and distinct from any other known designs of the time.

Apart from their form, the tattoos are also remarkable in terms of composition. Using X-ray fluorescence spectrometry, μRaman spectroscopy, and scanning electron microscopy, scientists found that the pigment of the tattoos consisted of magnetite, a mineral with high iron content, combined with pyroxene silicates. Charcoal, the most common black pigment in tattooing since ancient times, was entirely absent.

“As far as the authors know, the use of a black pigment made from magnetite for tattooing has not yet been reported on South American mummies,” the researchers noted. They also added that the identification of pyroxenes in tattoo pigments is even rarer.

Despite the diligent work, the purpose of these tattoos remains uncertain. Their visibility suggests a communicative or decorative function, but without recognized cultural parallels, their meaning is a mystery. Still, the discovery offers an unprecedented glimpse into the personal and cultural expression of a woman who lived over 800 years ago in the Andes.