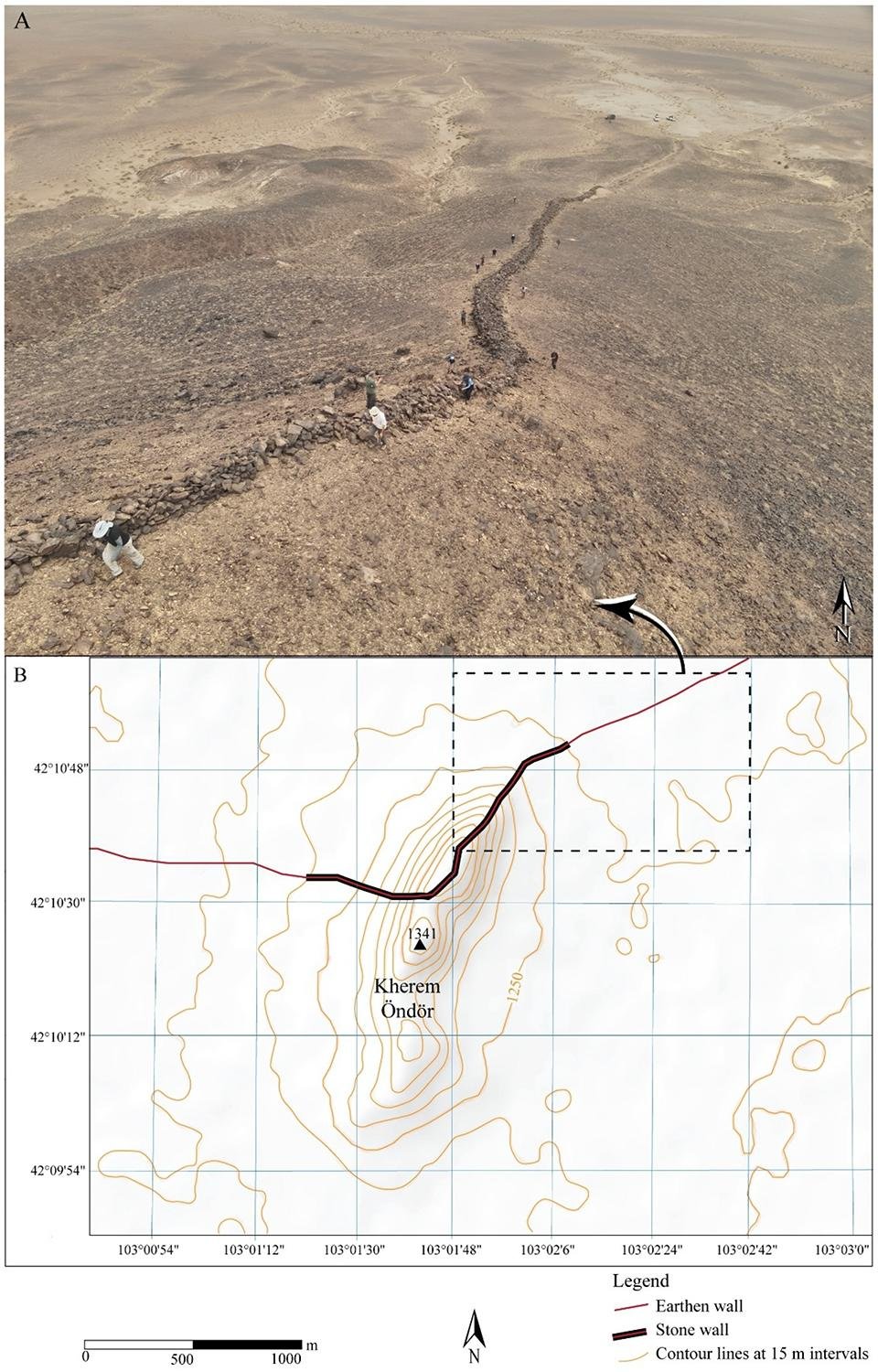

In Mongolia’s Gobi Desert is a 321-kilometer-long wall that, until recently, was one of East Asia’s least understood components of medieval infrastructure. Called the Gobi Wall, this enormous structure has mystified archaeologists for decades. But new research, published in the journal Land, is now giving valuable information about its construction, purpose, and historical context, redrawing the wall not as a simple defense fortification, but as a sophisticated tool of statecraft used by the Xi Xia dynasty.

The international research was carried out by Professor Gideon Shelach-Lavi and Mr. Dan Golan of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s Department of Asian Studies, in collaboration with Professor Chunag Amartuvshin of the National University of Mongolia and Professor William Honeychurch of Yale University. The study combined satellite imagery, ground surveys, and targeted excavations to investigate the structure in Mongolia’s Ömnögovi province.

According to the findings, the Gobi Wall was constructed primarily during the 11th to 13th centuries CE, under the Xi Xia dynasty, or Western Xia Empire. The Tangut-led empire controlled parts of Western China and southern Mongolia at the time. The main construction of the wall took place during a period of significant geopolitical transformation, when frontier defense and territorial management were crucial to the survival of the empire.

The study arrives at an unanticipated conclusion: that the Gobi Wall was part of a broader network of watchtowers, forts, trenches, and garrisons. These elements were identified on natural landforms such as mountain passes and sand dunes and were placed along routes chosen depending upon the availability of key resources such as water and wood. The wall itself was built with locally sourced materials like rammed earth, stone, and timber—a remarkable feat given the harsh environment and remote position of the region.

Excavations at key sites, like two garrisons designated as G05 and G10, found ceramics, coins, and remains of animals spanning nearly two thousand years, from the 2nd century BCE to the 19th century CE. While these finds indicate that the region was inhabited periodically over the centuries, radiocarbon dates and numismatic evidence attest that the principal period of use for the wall was at the height of Xi Xia’s rule.

The researchers argue that the function of the wall extended far beyond defense. “It exemplifies a mode of Xi Xia statecraft that used architectural investments to manage resources, population movement, and territorial boundaries,” they wrote. Rather than viewing frontier walls as rigid boundaries, the researchers propose viewing them as zones of control and interaction, dynamic infrastructures that shifted in response to political and environmental needs.

This new interpretation has broader implications for how scholars conceive of ancient infrastructure networks across Inner Asia and beyond. With these findings, the Gobi Wall joins the ranks of the world’s great historical infrastructures, not just for its dimensions and endurance, but for its role in shaping the politics and ecology of the time.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.