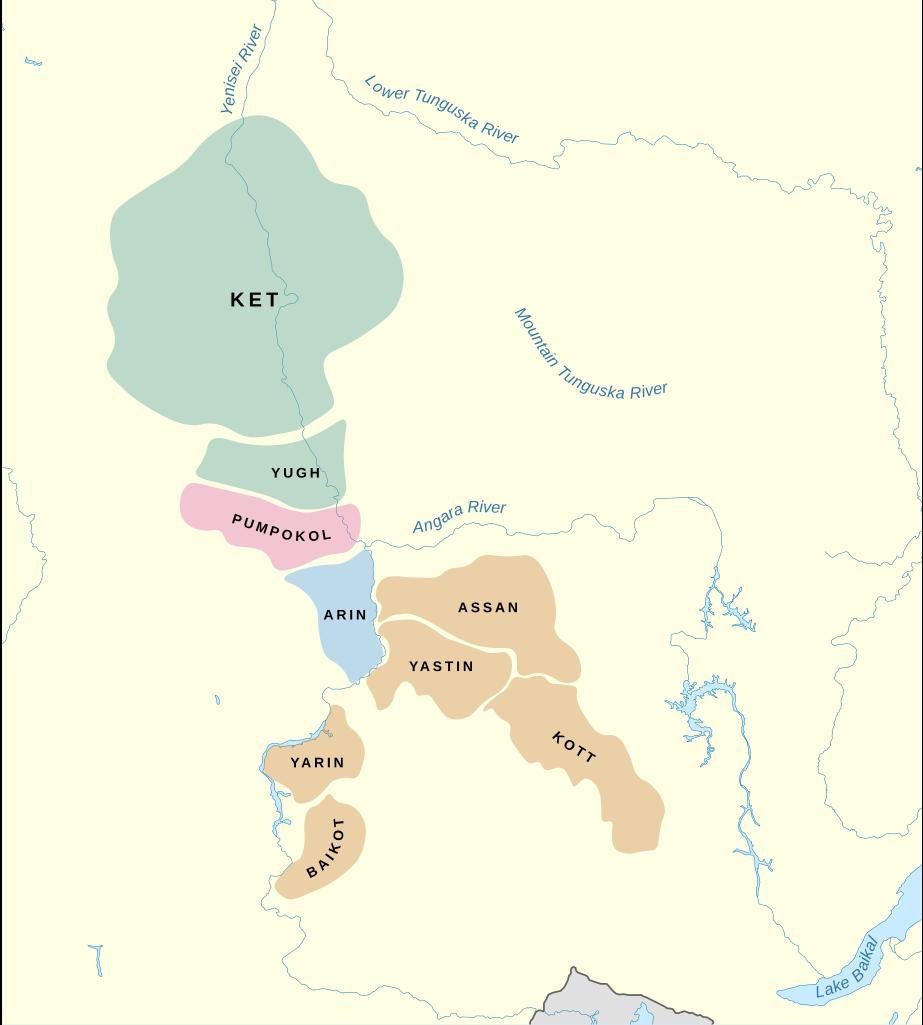

A newly published linguistics study suggests that the European Huns, previously thought to have Turkic origins, instead shared a common Paleo-Siberian language with the ancient Inner Asian Xiongnu. The research, conducted by the University of Cologne’s Dr. Svenja Bonmann and the University of Oxford‘s Dr. Simon Fries, presents strong linguistic evidence that both groups spoke Old Arin, an extinct language within the Yeniseian language family.

The study, published in the journal Transactions of the Philological Society, brings together linguistic evidence and previous archaeological and genetic evidence, and offers a cohesive narrative about the movement and linguistic heritage of the ancient nomadic powers. Dr. Fries said, “Our study shows that alongside archaeology and genetics, comparative philology plays an essential role in the exploration of human history. We hope that our findings will inspire further research into the history of lesser-known languages and thereby contribute further to our understanding of the linguistic evolution of mankind.”

The Xiongnu dominated parts of Inner Asia between the 3rd century BCE and the 2nd century CE, and the Huns arrived centuries later with a powerful empire in southeastern Europe during the 4th and 5th centuries CE. Contrary to earlier expectations linking both groups to Turkic or Mongolic roots, this new study turns the proposition around by identifying consistent linguistic features linking them to a shared Yeniseian origin.

Bonmann and Fries analyzed a wide range of linguistic evidence—loanwords in ancient languages, Chinese glosses, personal names, and geographic terms. Five natural element loanwords for “lake,” “rain,” and “birch,” found in both Turkic and Mongolic languages, have phonological characteristics consistent with Old Arin. They argue that these are not Yeniseian borrowings, but rather the reverse—proof of the prestige of the Arin language in Inner Asia prior to Turkic expansion.

The so-called “Jie couplet,” a rare linguistic relic preserved in a Chinese chronicle, was long assumed to be Turkic. But Bonmann’s research found that its grammatical structure is closer to Arin. In addition, personal names of Hun leaders—including Attila—are now thought to have derived from Arin roots. Attila, the research suggests, may not be a Germanic nickname meaning “little father,” as often believed, but rather a Yeniseian term meaning “somewhat fast” or “quick-ish.”

Toponymic evidence weighs in as well. Hydronyms and place names stretching from the Altai-Sayan region—long assumed to be a Xiongnu core homeland—west to Europe reflect Arin linguistic patterns. These onomastic patterns trace the westward migration of the Huns and leave a record of cultural and linguistic continuity from Inner Asia to the Carpathian Basin.

This linguistic find is also aligned with recent genetic studies. A 2025 study by Gnecchi-Ruscone and colleagues discovered direct genetic connections between Xiongnu elites in Mongolia and those who had been buried in the Carpathian Basin, suggesting that the European Huns were descended biologically—and now linguistically—from the Xiongnu.

These languages were spoken in Siberia before Uralic, Turkic, and Tungusic tribes migrated. “This was long before the Turkic peoples migrated to Inner Asia and even before the splitting of Old Turkic into several daughter languages. This ancient Arin language even influenced the early Turkic languages and enjoyed a certain prestige in Inner Asia,” explained Dr. Bonmann.

The research’s interdisciplinary approach—based on linguistic, archaeological, and genetic evidence—offers a powerful model for uncovering ancient pasts where written records are scarce. It not only asserts more firmly that the Huns and Xiongnu were part of a continuous cultural and linguistic lineage, but also presents a challenge to explore Eurasia’s linguistic landscape.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.

It was already known that The Huns were the offshoots of the western Xiongnu empire, immigrating westward, over Transeurasian steppes.

The Huns, just like the original Asian Huns/ Xiongnu, were already a confederation with lots of clans from different linguistic backgrounds.

The leading clans were thought to be Turkic, in addition to some member clans. Assuming both these factions were consisting a “nation” like system like the modern states, with a single language spoken within, would be a huge fallacy.

While the researchers have some evidence and arguments based upon them, they need more to actually challenge and change the narrative.

That’s what I thought so as well, this article seems a lil late to the news

Fascinating.

I know there’s a trend to value “hard” science in the field of archaeology and the study of history overall, but I think it’s worth remembering that philology should not be overlooked as a tool in uncovering the past There’s so many areas that can be re-examined and re-evaluated with this in mind, especially when there’s a paucity of hard evidence.

Nice information

I am assuming Finnish is somehow also involved? But must be wrong as no mention was made??

The ChiComs have been pushing the Xongnui propaganda for a decade and none of it’s true. The Huns were never a monolithic ethnicity but certainly not Chinese and when the Huns retired from Western, Central and Eastern Europe it was to their homelands on the Caspian and Kazakh Steppe melted where they melted into the Tartar emergence.

Very fascinating! Do you have a link to a fuller article?