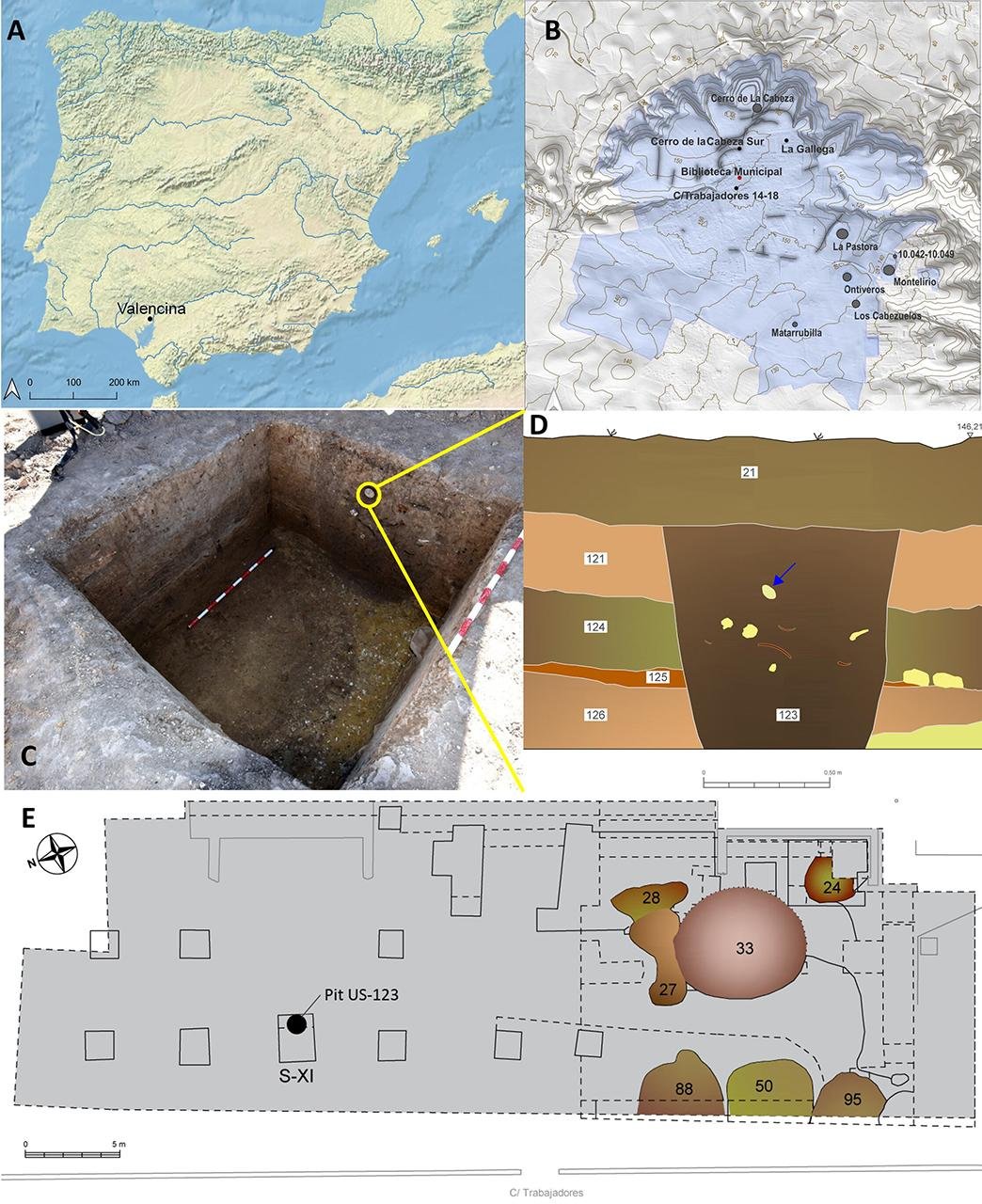

An exceptional archaeological discovery at the Copper Age mega-site of Valencina in south-west Spain provides fresh insight into prehistoric Iberian populations’ relation to the sea. Spanish archaeologists discovered a rare sperm whale tooth during a 2018 excavation at the Nueva Biblioteca sector, estimated to be the first ever discovered in Late Prehistoric Iberia.

Dating between 5,300 and 4,150 years ago, the tooth was recovered from a non-burial pit and appears to have had a complex post-mortem journey. Taphonomic and technological analyses revealed that the whale died of natural causes, likely sank to the seafloor, and was scavenged by marine life afterwards. The tooth also bears signs of bioerosion by worms and barnacles, and even bite marks likely caused by sharks.

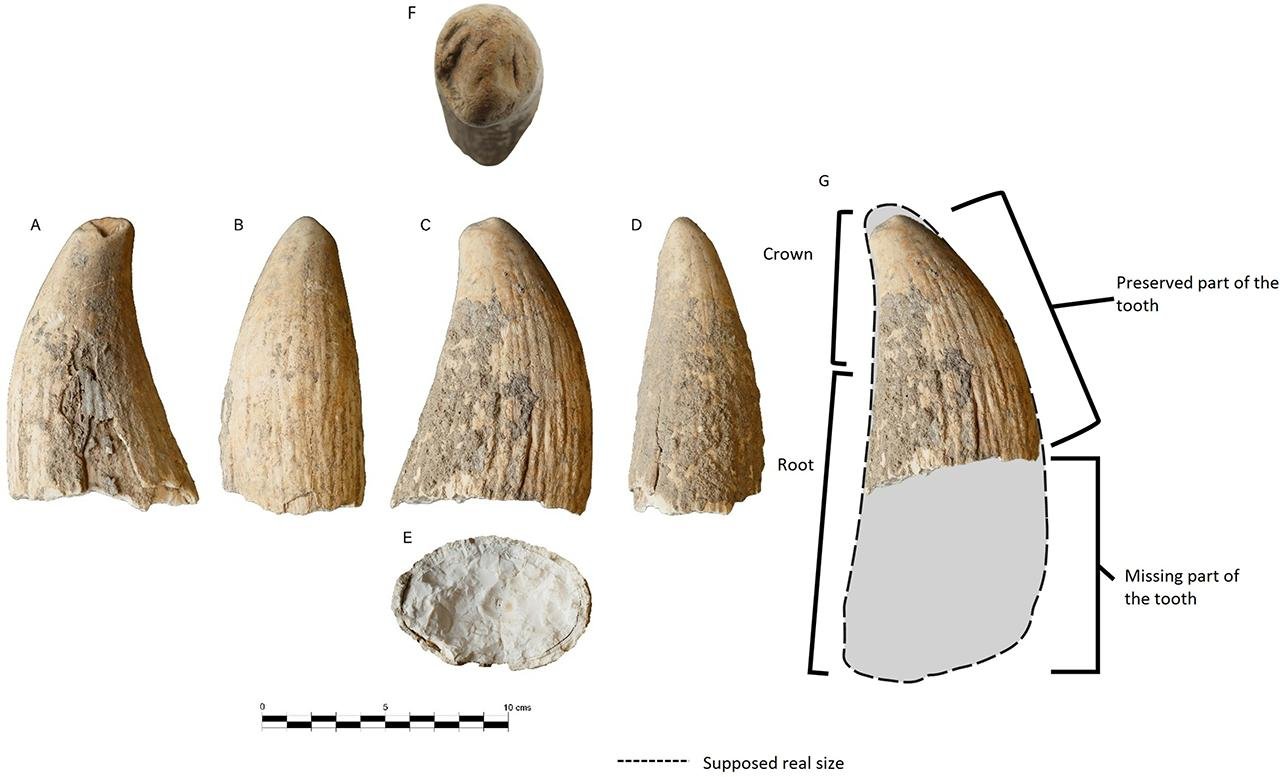

According to the study published in PLOS ONE, the recovery and modification of the tooth represent a significant cultural occurrence. Having washed ashore, the large, half-kilogram sample, 17 centimeters high by 7 centimeters wide, was recovered by Copper Age artisans, who worked on it with care. Scientists identified distinct cut marks and holes drilled in it, proving that the tooth had been intentionally modified, possibly to take out pieces to use as ornaments or symbolic items.

“The discovery of this piece underlines the presence of the sea in the worldview of the communities that lived in or frequented Valencina in the 3rd millennium BCE,” wrote the researchers in their study. This interpretation is supported by the use of marine-themed materials at other nearby archaeological sites, including capstones at La Pastora and Matarrubilla, and shell offerings found near the famous “Ivory Lady” burial at Montelirio.

Multidisciplinary methods were crucial to the study. Researchers used photogrammetric 3D modeling, geological sampling, and contextual archaeological surveying to follow the full life cycle of the tooth, from the whale’s death and subaquatic exposure to human manipulation and final reburial of the tooth in a pit. Roots and soil left impressions over time and even created a cemented crust on the surface.

While ivory from terrestrial animals such as elephants and hippos is common in prehistoric European archaeology, sea ivory is a rare phenomenon. This discovery thus adds another chapter in understanding how Copper Age societies valued the sea, not only as a resource but as a symbolic part of their cultural identity.

The fact that this sea object is present in an inland location suggests that early societies may have had larger networks of travel or trade than previously assumed. It also suggests a symbolic role for marine objects, potentially in conjunction with ritual or oceanic and sea creature-related beliefs.