The first people to set foot in the Americas crossed with them not only stone technology and survival skills across the icy expanse of the Bering Strait. Along with these, a new study published in Science indicates that they also carried a genetic legacy inherited from two extinct relatives—Neanderthals and Denisovans—that could have helped them survive in a new and unfamiliar environment.

The international research team, headed by the University of Colorado Boulder’s Fernando Villanea and Brown University’s David Peede, focused on the gene MUC19, which codes for mucin proteins involved in producing mucus. The proteins protect tissues from pathogens and may also play a role in immunity. Their findings suggest that Indigenous Americans inherited a version of the Denisovan-specific MUC19 that increased in frequency over time, perhaps because it offered an evolutionary advantage.

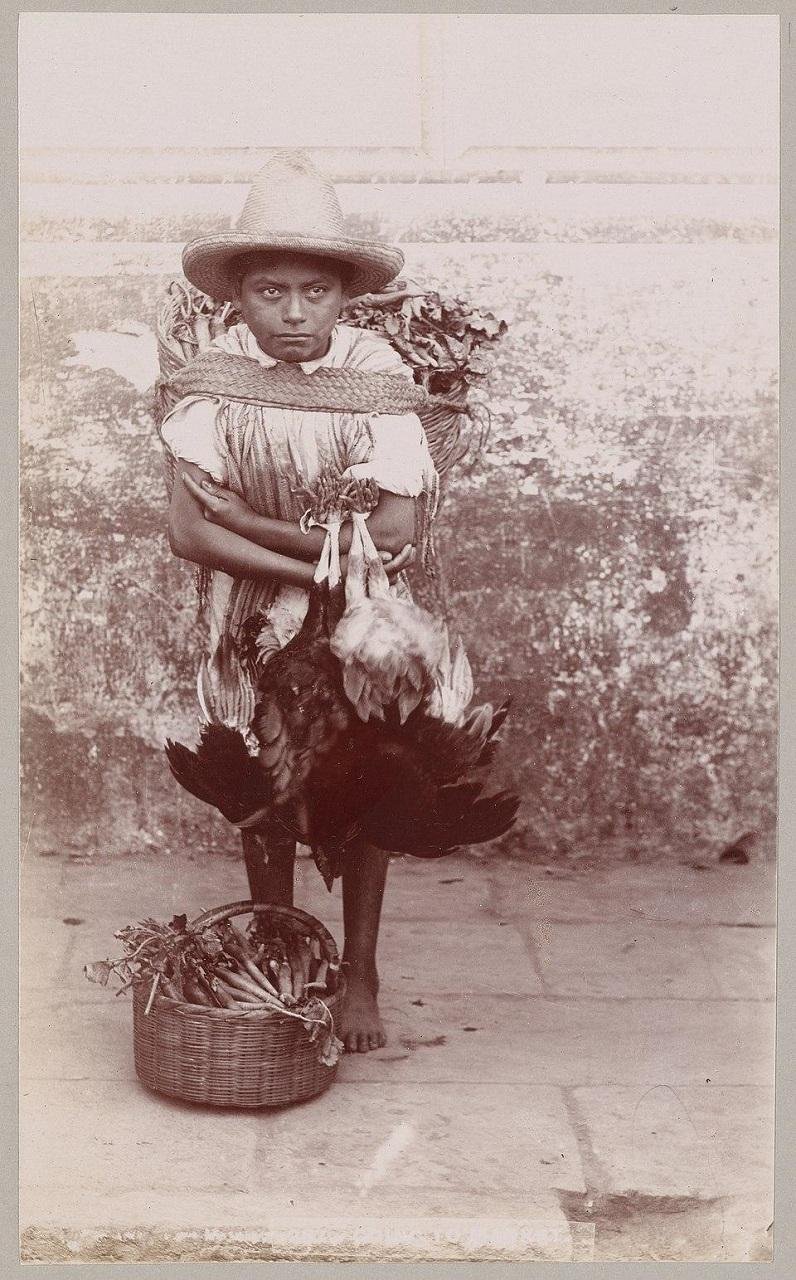

According to the study, one in three Mexicans today carries a copy of this Denisovan variant. It is found less often in others: about 20% of Peruvians and roughly 1% of Puerto Ricans and Colombians. Only about 1% of those of Central European ancestry have it. The difference, scientists suggest, reflects the higher proportion of Indigenous American DNA in Mexicans.

What amazed the scientists most was how the gene spread. The Denisovan DNA did not pass directly to modern humans but rather through Neanderthals. The Denisovan sequence is integrated within a larger Neanderthal-specific stretch of DNA, forming what Villanea described as “an Oreo, with a Denisovan center and Neanderthal cookies.” Genetic data suggest that Neanderthals first interbred with Denisovans and then passed on the combined DNA to humans. This is the first recorded case of a Denisovan gene entering humans with the help of a Neanderthal intermediary.

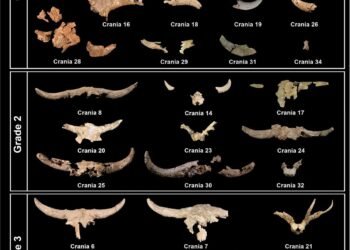

Researchers compared the genomes of ancient remains of 23 Indigenous Americans who lived before European contact, as well as genetic data from modern populations in Mexico, Peru, Colombia, and Puerto Rico. They also compared these with sequences from three Neanderthals and one Denisovan. Their research revealed that the segment of MUC19 that is associated with Denisovans is very long and contains variable number tandem repeats (VNTRs)—repeated segments of DNA that affect the manner in which the protein binds to sugars. Individuals who carry the archaic haplotype tend to have more VNTRs, which could potentially influence immunity.

The study provides proof that this package of genes underwent positive selection within Indigenous American populations—that is, it conferred some benefit that helped them survive. “In terms of evolution, this is an incredible leap,” Villanea said. “It shows an amount of adaptation and resilience within a population that is simply amazing.”

How this Denisovan variant reached so far in the Americas but not anywhere else is uncertain. Scientists indicate that the first inhabitants of the continent must have had to deal with new climates, foods, and pathogens, and that having the MUC19 variant helped them survive. Natural selection, over thousands of years, likely spread the gene through Indigenous peoples.

Though still enigmatic in many ways—Denisovans were identified only 15 years ago from DNA in a bone fragment in a Siberian cave—their genetic fingerprints remain. Up to 5% of the genome of some modern-day Oceanians is made up of Denisovan DNA. This latest research shows that their influence extended into the Americas, shaping the health and survival of Indigenous communities.

Villanea and his colleagues plan to look next at how different versions of MUC19 affect modern-day health, particularly among Latino and Indigenous American populations.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.

Great insight, and great story. The first people to migrate from Asia into North and South America were essentially inhabiting a new planet with a whole new set of physical and mental challenges. The fact that they occupied everything from the Arctic north to Tierra Del Fuego so quickly suggests a lot a genetic resilience. One of the great stories of life on Earth.

It would be interesting to test for Denisovan DNA among indigenous peoples from The Arctic and Alaska as well as tribes further south of the land bridge to track the migration of the Neanderthal/Denison genes from north to south in North America