A new study suggests that a hidden genetic mismatch between Neanderthals and early modern humans may have caused reproductive issues in their hybrid offspring—possibly contributing to the Neanderthals’ extinction around 40,000 years ago.

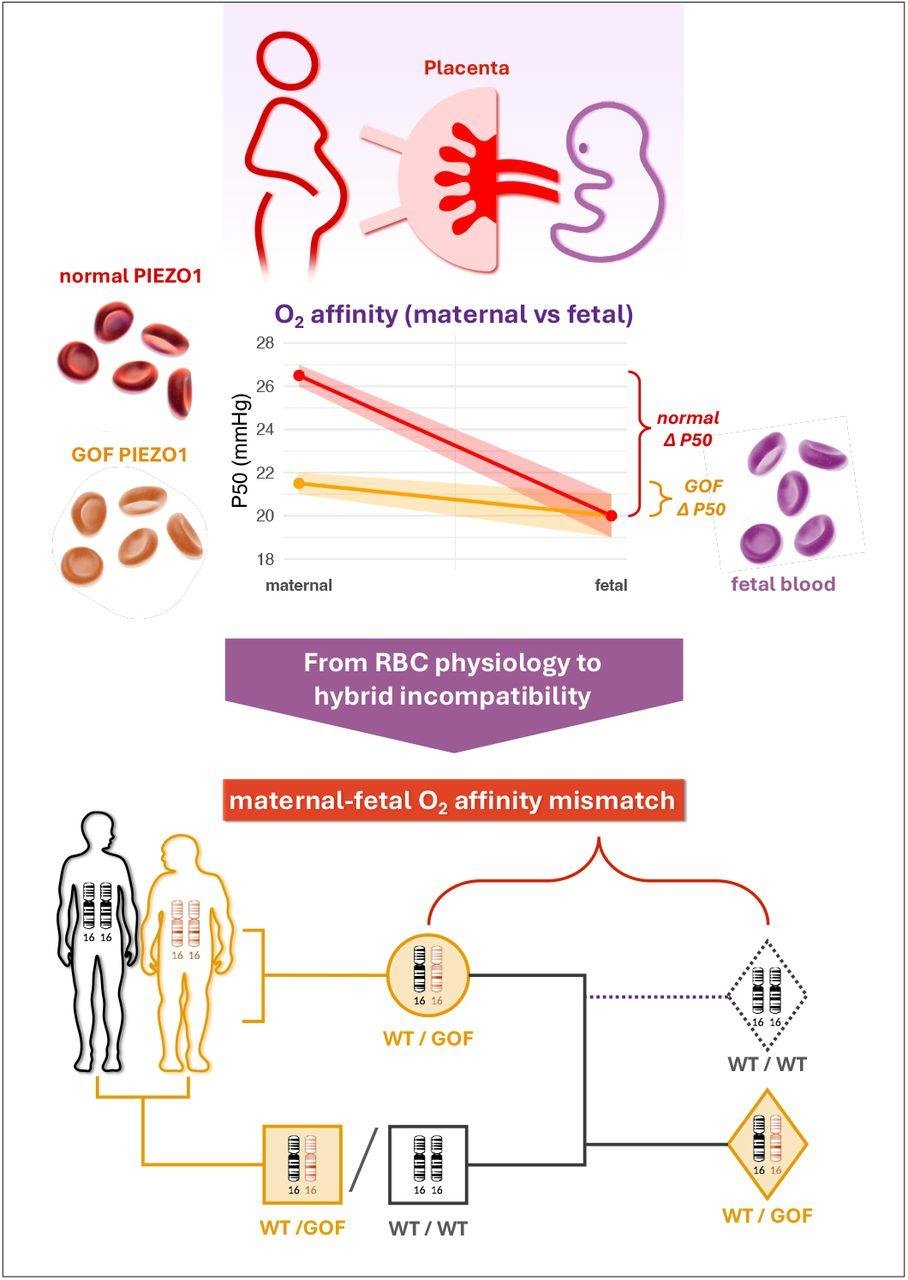

Researchers at the Institute of Evolutionary Medicine in Zurich examined the PIEZO1 gene, which affects how red blood cells transport oxygen. While both species carried versions of this gene, the scientists found significant differences that could have created problems when they interbred. The Neanderthal variant caused hemoglobin to bind to oxygen more tightly—an adaptation that could have helped them survive the freezing Ice Age conditions and food shortages. The modern human variant allowed oxygen to be released more efficiently into bodily tissues, enabling enhanced endurance and metabolism.

However, when these two forms met in hybrid pregnancies, they could have clashed. The researchers suspect that when a hybrid Neanderthal–human mother was pregnant with a fetus that had the modern human version of the gene, the placenta may have transferred less oxygen than required, causing hypoxia—a lack of oxygen that can result in fetal growth restriction or miscarriage. Laboratory tests validated this hypothesis: when PIEZO1 activity was increased in human red blood cells, oxygen binding was enhanced, replicating the Neanderthal-like effect.

Population genetics and computer models were also used in the study to examine the evolutionary consequences. Repeated maternal–fetal mismatches may have led to reduced fertility among hybrids, the simulations showed, which would gradually lower the Neanderthal allele frequency over generations. This process, known as frequency-dependent selection, could have silently weakened Neanderthal populations.

Modern human genomes today show almost no trace of the Neanderthal PIEZO1 variant, which indicates that it was strongly selected against. This incompatibility, the researchers noted, would not have caused a sudden collapse but rather a slow, compounding decline—”more like rust weakening a structure than a single catastrophic blow.”

The findings add another piece to the Neanderthal extinction puzzle, showing that subtle physiological factors, not just climate or competition, may have been involved. These genetic barriers would have reduced successful reproduction between humans and Neanderthals, limiting gene flow and undermining the survival of Neanderthals.

Significantly, the research also implies modern relevance. The same oxygen transfer issues with red blood cell function still underlie certain pregnancy complications today. By understanding how ancient genetic variants affected fetal oxygen delivery, scientists can potentially gain insights into maternal health risks in the modern day.

The study highlights how small genetic differences can have a profound influence on evolutionary outcomes. The PIEZO1 incompatibility may have been one of several hidden reproductive barriers that emerged when humans and Neanderthals first met in Eurasia some 45,000 years ago. While the two species shared genes, tools, and perhaps even cultures, their biology was not completely compatible.

In the end, such microscopic mismatches might have tipped the balance of survival. Homo sapiens proceeded to expand across the globe, while Neanderthals gradually vanished—leaving behind a genetic legacy that tells the story of connection and separation in the human family tree.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.

Hi.

This is an interesting essay. But in my opinion, we have to consider the rate of interbreed between a male Neanderthal with a female modern human. I think it was just small percentage, and it couldn’t affect to the extinction of Neanderthal. It means the most percentage of Neanderthal kept interbreed inside their population during their existence.

Thanks.