A recent study published in PLOS One reveals that Neanderthals and early modern humans began to reshape Europe’s ecosystems tens of thousands of years before the rise of agriculture. Rather than being passive foragers in an unspoiled wilderness, these early populations actually influenced vegetation patterns across the continent.

The international research team, comprising archaeologists, ecologists, and climate scientists from the Netherlands, Denmark, France, and the United Kingdom, used advanced computer simulations to investigate how interactions between climate, wildlife, fire, and human activity shaped prehistoric landscapes in Europe. Their conclusions refute the common theory that humans had little impact on their environment before the advent of farming.

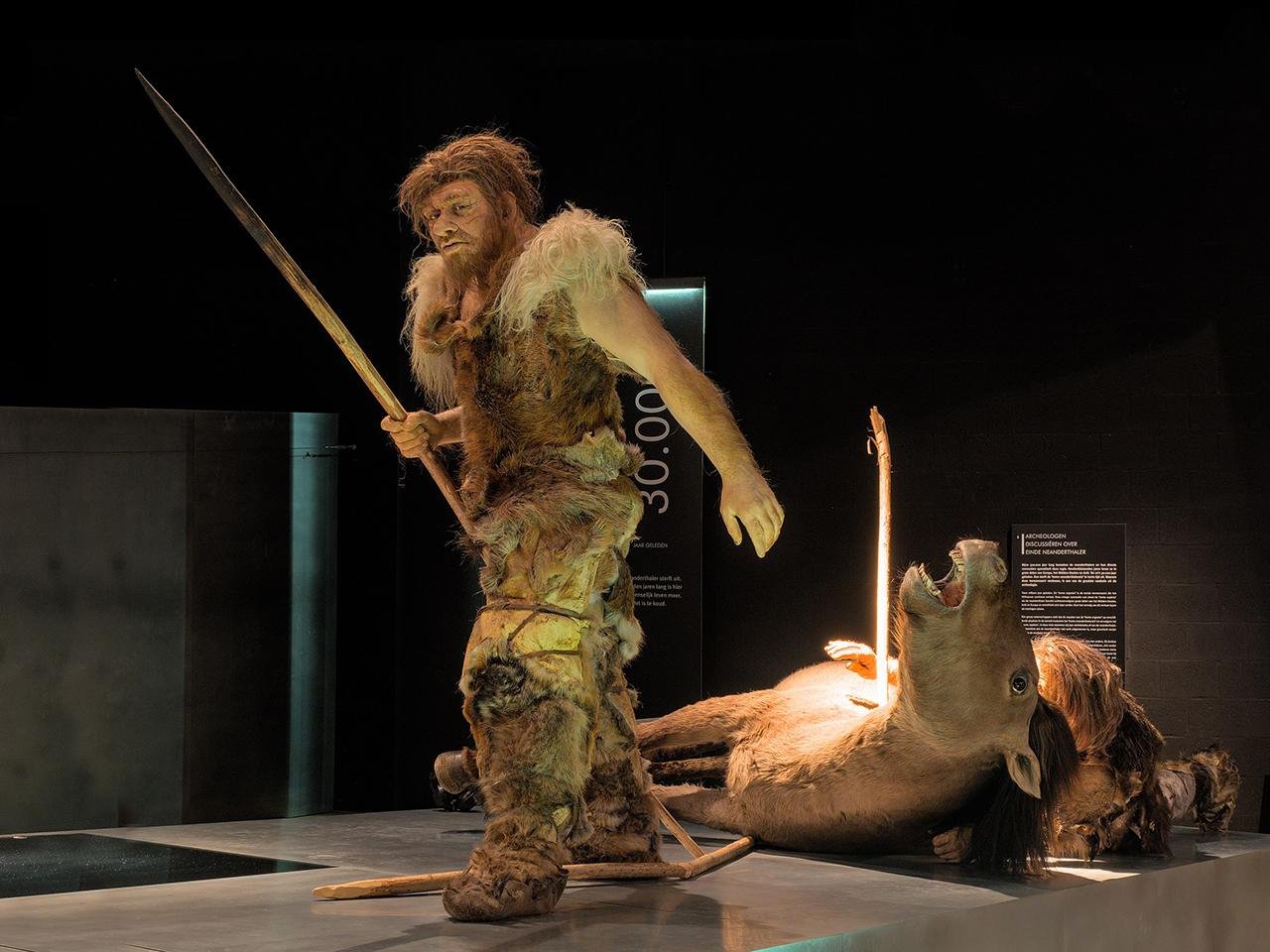

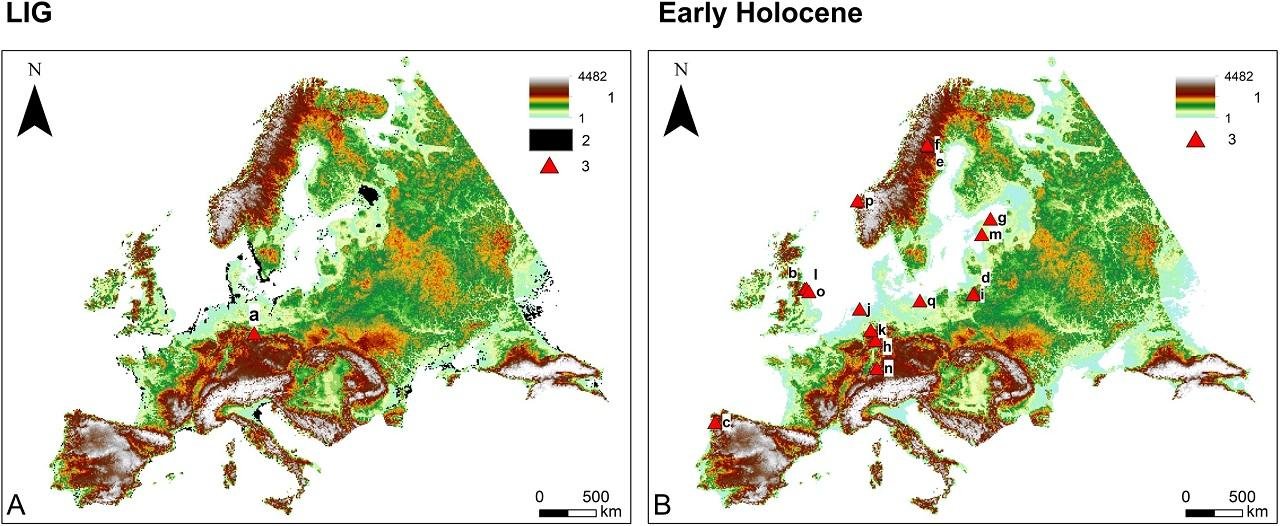

Led by Leiden University archaeologist Anastasia Nikulina, the researchers developed a sophisticated model called HUMLAND (HUMan impact on LANDscapes), which was adapted to simulate how hunter-gatherers interacted with their landscapes during two of the most important warm periods: the Last Interglacial (c. 125,000–116,000 years ago), when Europe was inhabited only by Neanderthals, and the Early Holocene (c. 12,000–8,000 years ago), when Mesolithic hunter-gatherers of our own species, Homo sapiens, occupied the continent.

By comparing the model’s simulations with pollen-based reconstructions of vegetation, they found striking mismatches between what climate alone could explain and what actually appeared in the fossil record. Even after adding the natural occurrence of wildfires, animal grazing, and climatic shifts, the results still fell short—until they added human behavior into the equation.

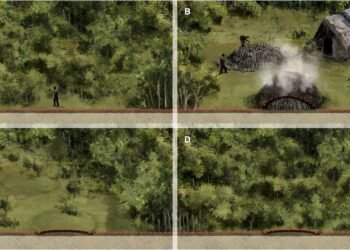

The researchers incorporated human activities such as burning vegetation to manage landscapes and hunting large herbivores such as bison, aurochs, and even elephants. These activities, the simulations showed, significantly altered vegetation composition and openness. Fire opened forests and maintained grasslands, while hunting reduced grazing pressure, allowing some areas to become denser with shrubs and trees.

According to the research, Mesolithic hunter-gatherers may have influenced up to 47% of plant-type distribution, while Neanderthals affected about 6% of plant distribution and 14% of vegetation openness. Even where human use of fire was limited, hunting alone had a large ecological impact. This indicates that both Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens modified similar areas around their campsites and shared preferences for open landscapes.

The study’s approach was not only novel for its use of vast data from across the continent, but also because it integrated artificial intelligence. Using a genetic algorithm, researchers were able to explore thousands of possible scenarios to identify those that best matched real-world pollen data. The combination of archaeology, ecology, and computational science allowed researchers to quantify the degree to which early humans shaped their environment.

Their findings depict prehistoric Europe not as an untouched landscape, but as a dynamic environment already transformed by humans. Their fires and hunting created ripple effects through ecosystems, changing plant communities and landscape structure long before the first fields were plowed.

These results are not just exclusive to Europe, but suggest that the human ecological footprint is a natural feature of our species, not an emergent development linked to agriculture or industry. As the researchers point out, comparing regions such as the Americas or Australia, which lacked earlier hominin populations before the arrival of Homo sapiens, could reveal more about how deeply ancient humans altered the natural landscape.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.