Excavating at Horvat Tevet in the Jezreel Valley, archaeologists have discovered an exceptional 7th-century BCE cremation burial that is changing current knowledge about Assyrian control in the Southern Levant. Dating to Iron IIC, the find is the richest and most varied cremation assemblage known from the region so far, outshining all other comparable burials in the Levant. Its objects, which include fine local pottery and high-value luxury imports, attest to a far-reaching trade network extending from Mediterranean ports to Neo-Assyrian centers in Mesopotamia.

The site of Horvat Tevet lies only 15 kilometers from Tel Megiddo, the Assyrian provincial capital during the 7th century BCE. By this time, many of the earlier urban centers in the valley had diminished or been abandoned, feeding into long-standing arguments that Assyrian administrators invested little in these territories and exploited them primarily for agricultural production. However, the cremation burial uncovered in the site’s Level 3 provides a strong counterpoint to the idea of regional neglect.

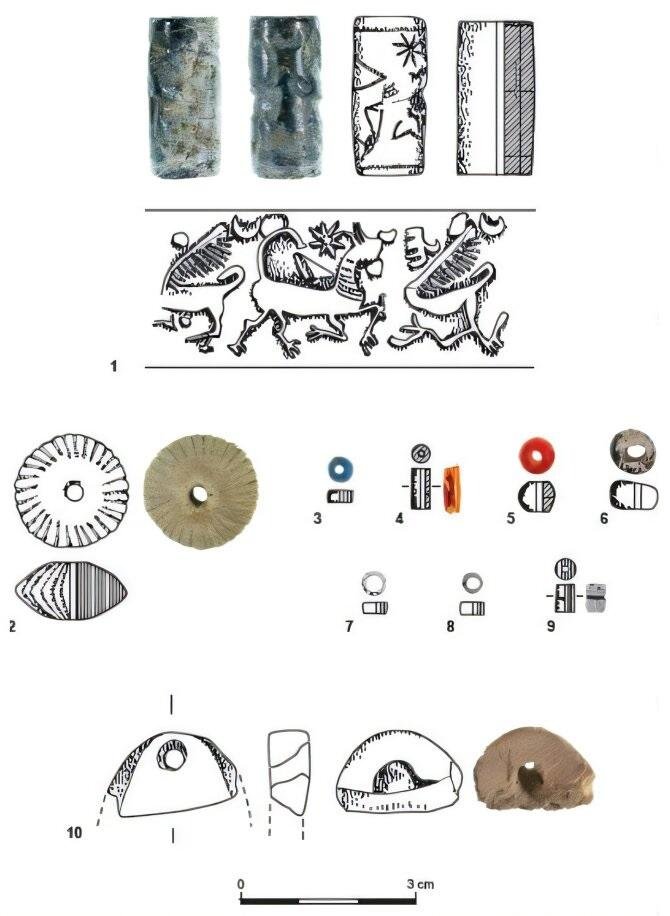

The burial itself was unusual, since cremation was an uncommon practice in the inland Southern Levant at that time. It consisted of two pits, with one pit containing articulated remains of an adult and the other pit containing the remains of a cremated individual. The cremation pit included three urns and a small niche filled with juglets. Although one urn contained only simple local items, the other two were filled with a remarkable assemblage of goods rarely seen in rural contexts. Among them were an amphoroid krater with colored bands, several juglets and bottles, bronze jewelry, dozens of beads, a glazed Assyrian bottle, a Neo-Assyrian cylinder seal, a stone weight, and a faience alabastron depicting scenes of birds and papyrus.

These luxury items, a number of which would normally be associated with elite burials in major Assyrian cities, display strong associations with imperial trade and administrative networks. Items such as the seal and stone weight hint at the profession of the deceased—possibly a merchant, an official, or someone who navigated both roles within the Assyrian system. The selection of goods seems to reflect not only personal identity but also deliberate connections to the broader imperial world centered on Megiddo.

It is striking to contrast the opulence of the burial with the sparse remains from everyday life at Horvat Tevet. The settlement itself indicates little wealth in the Iron IIC; however, the burial implies that individuals held significant status related to Assyrian provincial structures. The presence of such a high-status cremation in the rural hinterland may even indicate that the deceased was transported from the urban center at Tel Megiddo, underlining symbolic links between administrative authority and agricultural zones.

Taken together, the contents and context of this burial provide a new perspective on how the Neo-Assyrian Empire administered the Jezreel Valley. Far from being abandoned, the region might have been subject to a calculated strategy of reinforcing imperial control over its fertile lands and trade corridors. The impressive cremation at Horvat Tevet, with links to both local communities and imperial networks, underlines the region’s significance and calls for the revision of long-standing views of Assyrian disengagement in the Southern Levant.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.