Excavations at the ancient Red Sea port of Berenike in Egypt are rewriting scholars’ understanding of exotic pet keeping in the Roman world and uncovering surprising connections between Roman Egypt and the Indian subcontinent. Dozens of monkey burials from the site, analyzed in a recently published study, demonstrate that high-ranking Romans once kept imported Indian macaques as companions, an expression of wealth, status, and access to long-distance trade networks.

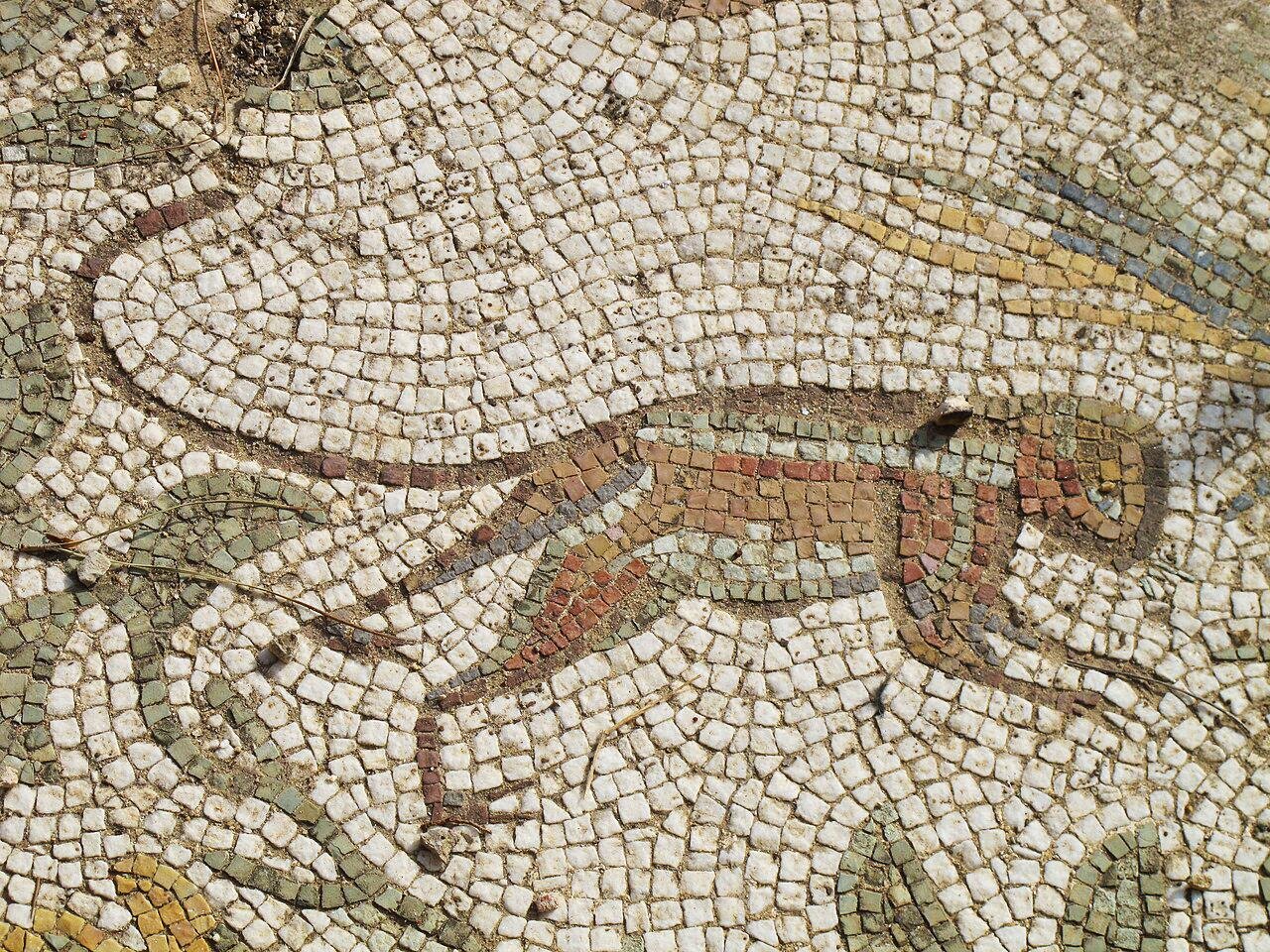

The animal cemetery at Berenike was discovered outside the ancient harbor town in 2011 and has since yielded close to 800 animal burials. Of those, 35 monkeys were carefully interred, dated to the first and second centuries CE. During that period, the port was an important hub in Roman trade with the Indian Ocean world. At this time, Berenike hosted a substantial Roman presence, including military personnel tasked with securing commercial routes.

The detailed osteological analysis led to the identification of most of these monkeys as species of macaques native to India rather than Africa. This goes against earlier assumptions that Roman pet monkeys were solely African, such as Barbary macaques. The Berenike discoveries now provide the first direct zooarchaeological evidence that live nonhuman primates were transported from India to Roman Egypt, reflecting an unprecedented degree of organization and demand.

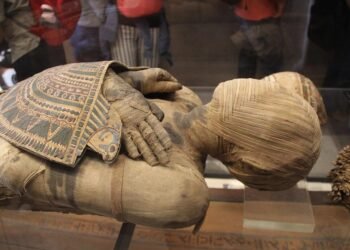

The burials themselves suggest that these animals held a special place in local society. Around 40 percent of the monkey graves contained objects placed deliberately alongside the remains, a striking contrast to cats and dogs at the same cemetery, which rarely included grave goods. Items found with the monkeys included collars used for restraint, food offerings, and visually striking shells likely valued for their iridescence. In several cases, the monkeys were buried with other animals—such as kittens or a piglet—interpreted as their own companion animals, underscoring the care and symbolism attached to them.

Such treatment suggests ownership by elite individuals, possibly Roman officers stationed at the port, for whom the exotic pets served as a social marker. Keeping a monkey imported from across the sea would have underlined both wealth and connections in a remote outpost of the empire.

Not all evidence suggests an easy life, however. Skeletal signs of nutritional stress were identified in some individuals, likely linked to dietary deficiencies. Rather than indicating neglect, researchers argue these issues reflect the practical difficulty of supplying fresh fruits and vegetables in an isolated desert harbor where such resources were scarce.

The Berenike monkeys thus provide an exceptionally rare and intimate view of Roman social behavior, global trade, and human-animal interaction from almost two millennia ago.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.