A new scientific study has shed light on the everyday health challenges faced by Roman soldiers stationed at Vindolanda, a fort near Hadrian’s Wall in northern England, through ancient sewage deposits. Researchers have uncovered clear evidence that the fort’s occupants suffered from widespread intestinal parasite infections linked to poor sanitation and contaminated water.

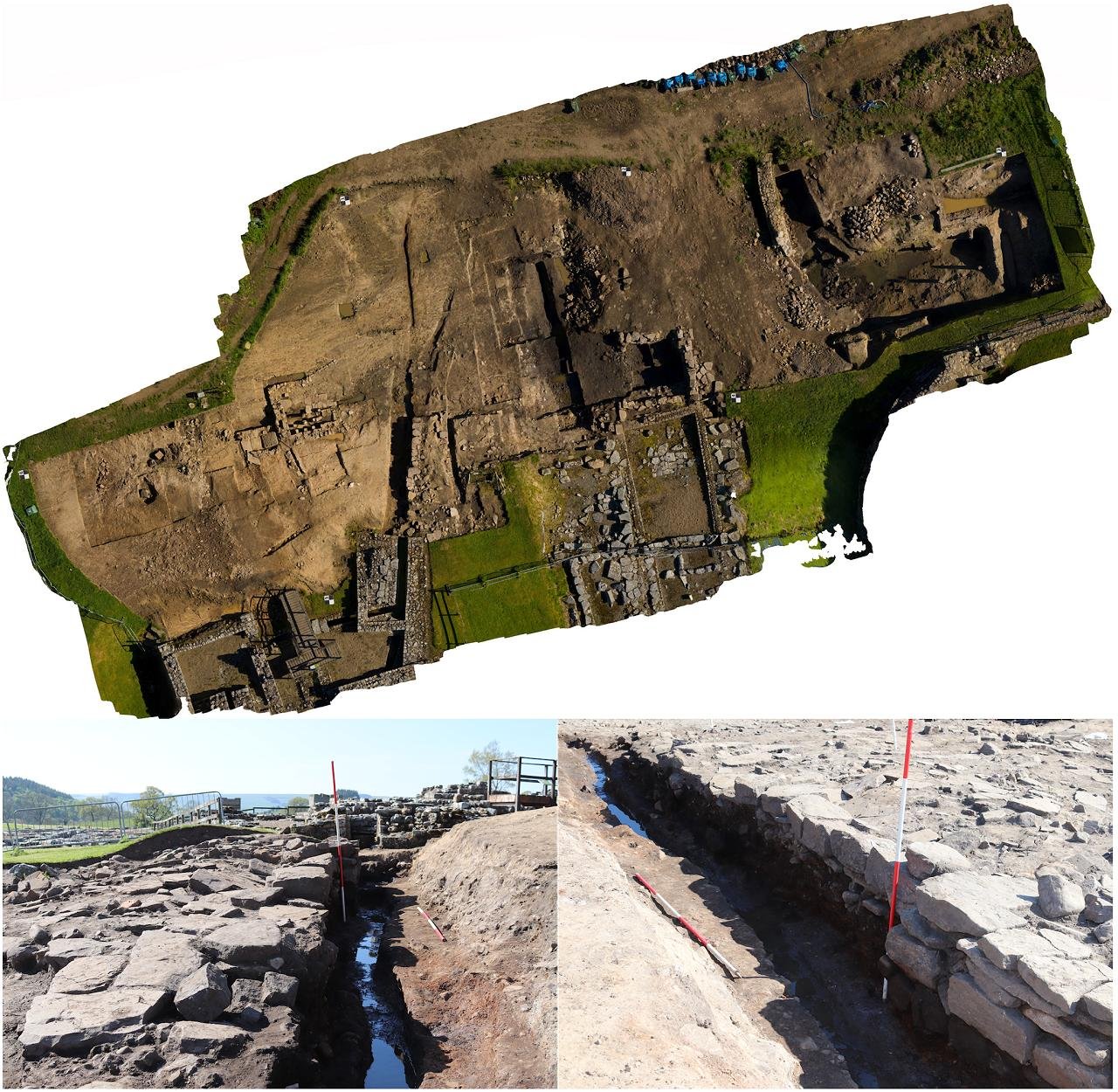

This research examined sediment taken from a stone drain that was linked to a third-century-CE communal latrine attached to the bath complex at Vindolanda. Almost nine meters in length, it would have still carried waste away from the latrine and into a nearby stream. Fifty samples taken along its length were examined using a combination of microscopic analysis and biochemical testing, which enabled scientists to identify parasites preserved in human waste nearly two millennia old.

The findings showed roundworm and whipworm, both parasitic worms that spread through contact with human feces, along with the microscopic protozoan Giardia duodenalis, also known to cause severe diarrhea. Roundworm and whipworm have been found at other Roman-period sites in Britain, but this is the first time Giardia has been confirmed in Roman Britain. The parasite is spread most easily through contaminated drinking water and can quickly result in the infection of large numbers of people.

Over a quarter of these samples contained evidence of parasite eggs, demonstrating that intestinal infections were not an isolated incident, but a persistent issue at the fort. Another sample, from an earlier, first-century-CE defensive ditch at Vindolanda, also contained roundworm and whipworm, indicating that sanitation-related illness existed during the earliest occupation of the site.

Vindolanda, situated just south of Hadrian’s Wall, was manned by auxiliary units recruited from across the Roman Empire. The fort is renowned for the remarkable preservation of organic materials, including wooden writing tablets and leather footwear, which provide a rare glimpse into what life was like on Rome’s northern frontier. These new findings add a biological dimension to this picture by revealing how disease may have affected soldiers’ strength and readiness.

The researchers point out that all the parasites identified are transmitted via the fecal–oral route and reflect poor hygiene and waste management. In contrast to other large urban Roman centers in Britain, such as London or York, where evidence of foodborne parasites from meat and fish has been found, Vindolanda’s parasite profile is dominated by infections spread directly between people. This pattern very closely resembles that seen at other Roman military sites across Europe.

Beyond the recording of ancient disease, the study indicates the benefits of sampling several points in archaeological drains. Such methods have the dual benefit of detecting parasites and informing reconstructions of how sanitation systems functioned.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.