Archaeologists excavate the ancient city of Smyrna underneath the modern urban fabric of İzmir and have uncovered a rare mosaic-floored room that offers new insights into Late Antique daily life and belief systems. The discovery was made along the Agora’s North Street during year-round excavations conducted as part of Turkey’s “Heritage for the Future” project, which protects and researches archaeological remains hidden within densely built cities.

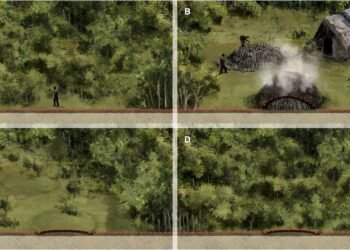

The newly uncovered mosaic floor measures three by four meters and consists of interlocking twelve-sided geometric panels, a decorative motif widely used during the Late Roman period. At the center of the design is a striking Solomon’s Knot motif, formed by intertwined loops. This symbol appears across many cultures and historical periods and is commonly interpreted as an apotropaic sign, intended to protect people and spaces from misfortune, envy, and harmful forces often described as the “evil eye.”

The mosaic belongs to a building dated between the fourth and sixth centuries CE, when Smyrna was a well-planned urban center reconstructed after the time of Alexander the Great. The main archaeological investigations at the site have concentrated on the agora and the ancient theater, two core elements of civic life in the classical world. While the exact use of the building is unknown, its position on one of the city’s principal streets indicates that it was an important structure, either as a private residence or a semi-public space.

The floor, apart from having this central knot, features an arrangement of plant-based motifs, geometric ornaments, and small cross figures around the main symbol. Although the crosses later came to be closely associated with monotheistic religions, their inclusion here indicates the complex visual language in which traditional symbolic conventions coexisted with a new, developing religious iconography. The combined motifs seem to have been selected primarily for the spiritual protection of the building and its users.

One of the most remarkable aspects of the find is evidence that the mosaic room was reused nearly 1,500 years after it was first laid. In the nineteenth century, structures linked to a non-Muslim hospital or nearby residences were built directly over the ancient floor. Traces of wall plaster applied on top of the mosaic indicate that the design was uncovered, recognized, and incorporated into later buildings, allowing it to remain visible and functional long after antiquity.

Only a few mosaic floors have been found in Smyrna, and the last similar discovery was made about seventy years ago. The appearance of another mosaic room after such a long time has therefore become a significant event for the researchers. Excavations are planned to be expanded in 2026, and archaeologists hope that other rooms or structures related to it may come to light.

- To view the original image and learn more about this discovery, you can visit this page

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.