Archaeologists studying Iron Age skull fragments from two sites in northeastern Iberia have expanded the known range of a ritual once linked only to coastal communities north of the Llobregat River. New analysis connects the practice with inland groups known as the Cessetani and the Ilergetes. The remains come from Olèrdola in Barcelona province and El Molí d’Espígol in Lleida province. Both settlements date between the sixth and second centuries BCE, a period when several Iberian societies displayed human heads in public spaces.

Researchers examined five cranial pieces from Olèrdola and ten fragments from El Molí d’Espígol. The Olèrdola bones belong to one young male between eight and fifteen years old. The Molí d’Espígol material represents three people, including another young male. Cremation served as the main burial rite across Iberian territory, so preserved skulls form a rare source of biological data.

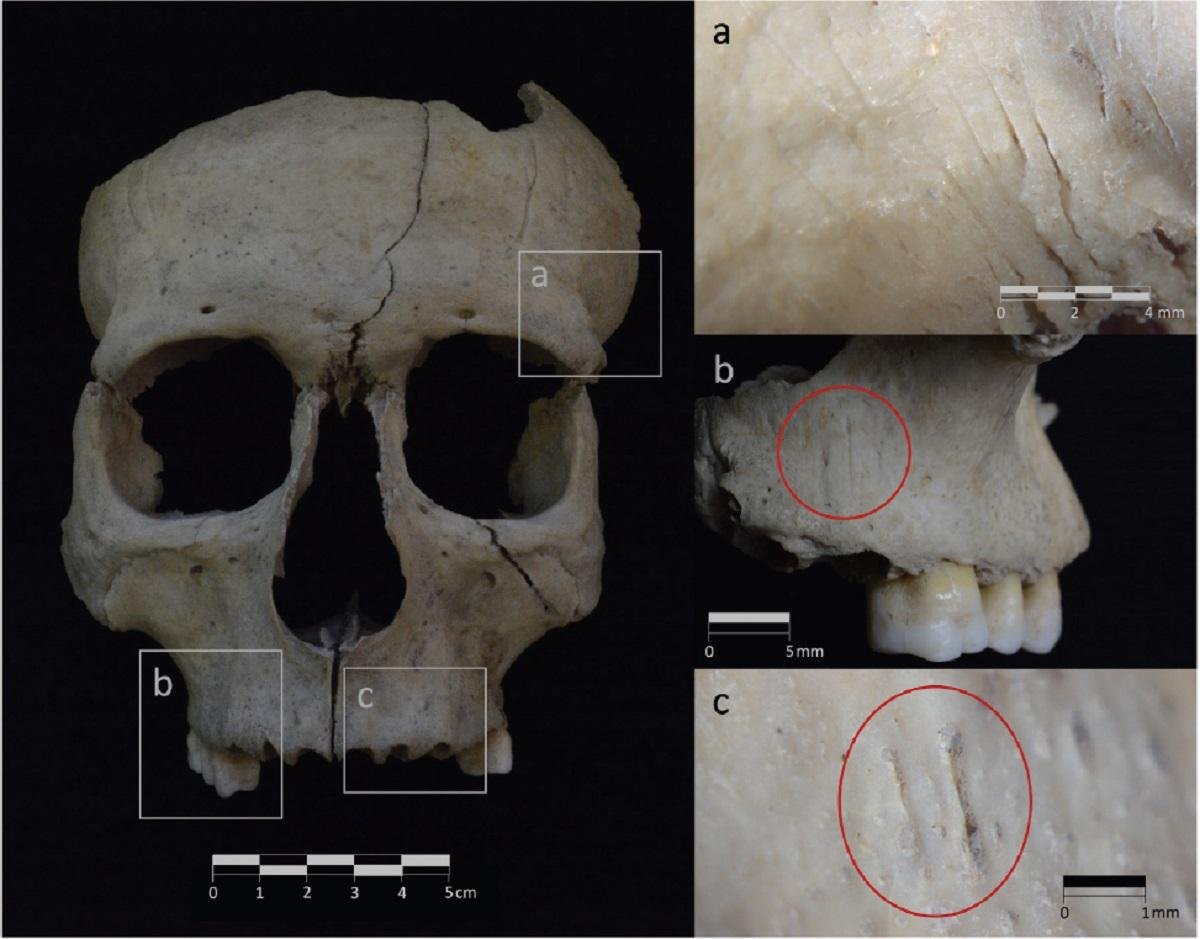

Microscopic study recorded cut marks formed close to the time of death. Many injuries match blows from sharp tools with a straight edge. On the Olèrdola skull, deeper cuts on the left frontal bone contrast with angled marks on the right side, which overlap in several places. Such variation suggests more than one strike and possibly more than one person involved. The lower rear skull did not survive, so clear proof of decapitation remains out of reach. Even so, trauma patterns support removal and later handling of the head.

Fine incisions appear around the forehead and jaw. Their size matches thin metal tools similar to needles recovered from other Iberian sites linked with head display. These marks show removal of soft tissue, including parts of the face. Comparable treatment appears in Iron Age contexts in France and Britain, which strengthens interpretation of ritual preparation rather than random violence alone.

Chemical testing of residues stuck to the Olèrdola bone identified plant resins from pine, along with oils and waxes of plant or animal origin. Such substances suit preservation or preparation for exhibition. The head likely received coating before placement in a visible location.

Isotope study adds another layer. Strontium values from teeth and bone do not match local geology near Olèrdola. Results point to childhood spent in a region with older rock formations. Movement during adolescence or transport of the head after death both fit the data. Similar mobility patterns appear in other Iberian cases linked with displayed skulls.

Context within each settlement strengthens the argument for public display. At Olèrdola, fragments came from the base of a tower flanking the main entrance. A head set above a gateway would send a strong message to visitors and rivals. At El Molí d’Espígol, remains clustered inside a large building near an open square. Architecture and location mark the area as socially important.

Earlier finds tied the custom mainly to the Indigetes and Laietani along the coast. The new evidence pushes the southern boundary inland and broadens the list of participating groups. Archaeologists have also identified female skulls in other sites, which raises questions about gender roles in warfare, punishment, or ritual selection.

Across Europe, display of enemy heads often signaled power and victory. Iberian material shows local variation in how communities prepared, placed, and later discarded skulls. Many ended up on floors, near walls, or inside filled storage pits after wooden supports decayed.

Work on these fragments combines bioanthropology, residue chemistry, and isotope science. Together, results build a clearer picture of a practice once known from scattered finds and classical descriptions. Each new case adds detail to social behavior, mobility, and symbolic acts among Iron Age groups in northeastern Iberia.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.