the ruins of the major city in southern Africa can be found in the mountains of southeastern Zimbabwe. Great Zimbabwe is the name given to this location. In the Shona language, the word Zimbabwe means “the big stone house,” and the country got its name from the ancient city. The city with enormous stone houses and enclosures was the capital of the Shona kingdom in parts of today’s Zimbabwe and Mozambique in the 11th century.

The city flourished and many people lived there until the 17th century when it was abandoned. But how did the people who lived there fulfill their needs? Great Zimbabwe is located in a climate-sensitive area, so ensuring a stable supply of water for so many people and animals must have been a problem.

A group of researchers from South Africa, England, Zimbabwe, and Denmark investigated this mystery in the article “Climate-smart harvesting and storing of water: The legacy of dhaka pits at Great Zimbabwe,” which was just published in the journal Anthropocene.

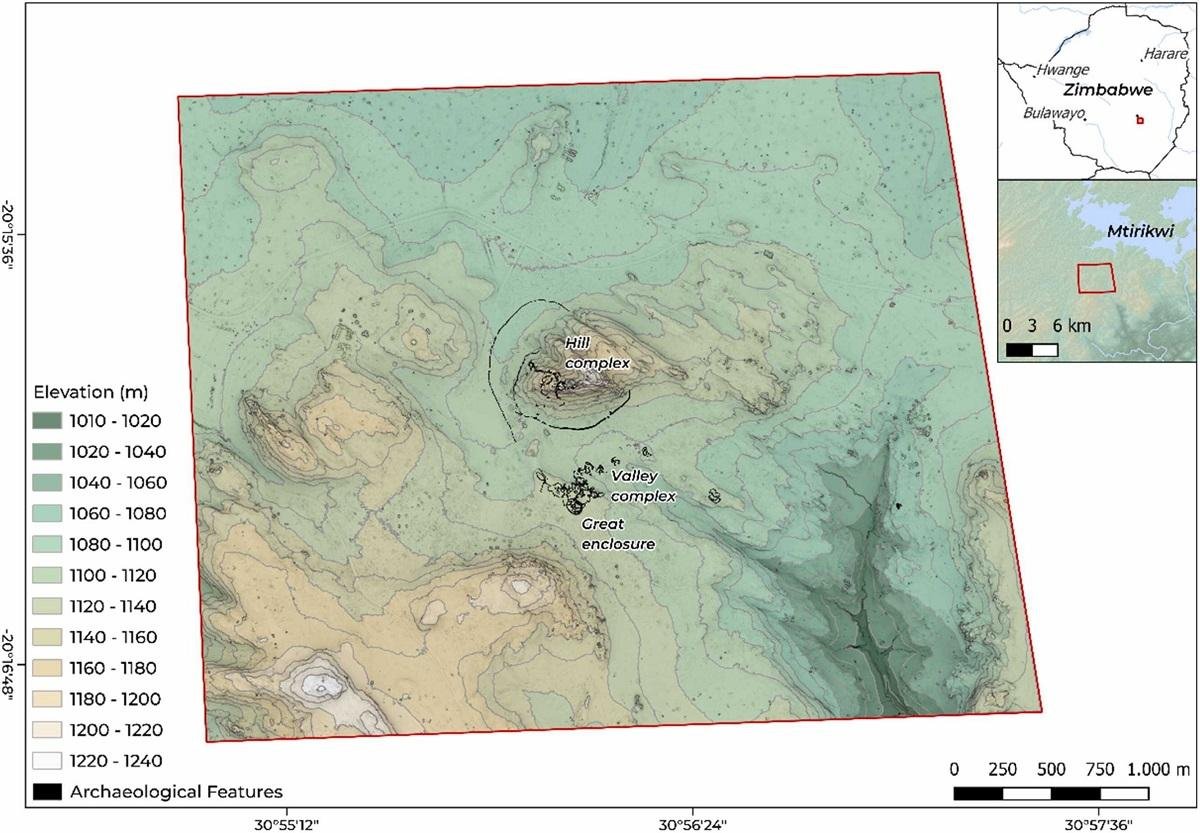

They investigated a number of large depressions in the landscape locally called “dhaka” pits using remote sensing methods and excavation.

The depressions were not previously studied because it was thought that they were made only to collect clay for city building. However, new research shows that this may not be the whole truth.

According to the findings, the pits were also used to store and manage water for the city. There are clear signs that the depressions have been excavated to collect surface water, and at the same time seep and store ground water for use during the dry seasons.

The researchers found more “dhaka” pits than were known before, and they have been found where small streams will naturally run through the landscape when it rains or where groundwater seeps out.

This, in combination with the location and construction of the depressions, convinced the researchers that the “dhaka” pits functioned as a clever system to ensure a stable water supply by storing more surface and groundwater that could be used outside of the rainy season.

The people of Great Zimbabwe thus devised climate-smart methods for storing and managing water in an area with three different climates, a very warm and dry season, a warm and wet season, and a warm and dry winter. Such a water supply may have been essential for the growth of an urban society that required a safe supply of water for its population, animals, and agriculture.

It is impressively conceived and shows that, much earlier than previously thought, management of the natural hydrological system was under control in the city. Perhaps they even managed it so well that other places in the world can now learn something from how they did it hundreds of years ago in Great Zimbabwe.

by Aarhus University. Note: Content may be edited

More information: Innocent Pikirayi et al, (2022). Climate-smart harvesting and storing of water: The legacy of dhaka pits at Great Zimbabwe, Anthropocene. DOI: 10.1016/j.ancene.2022.100357