Ancient human remains discovered in a Spanish cave have offered insights into enigmatic burial practices that extended across millennia.

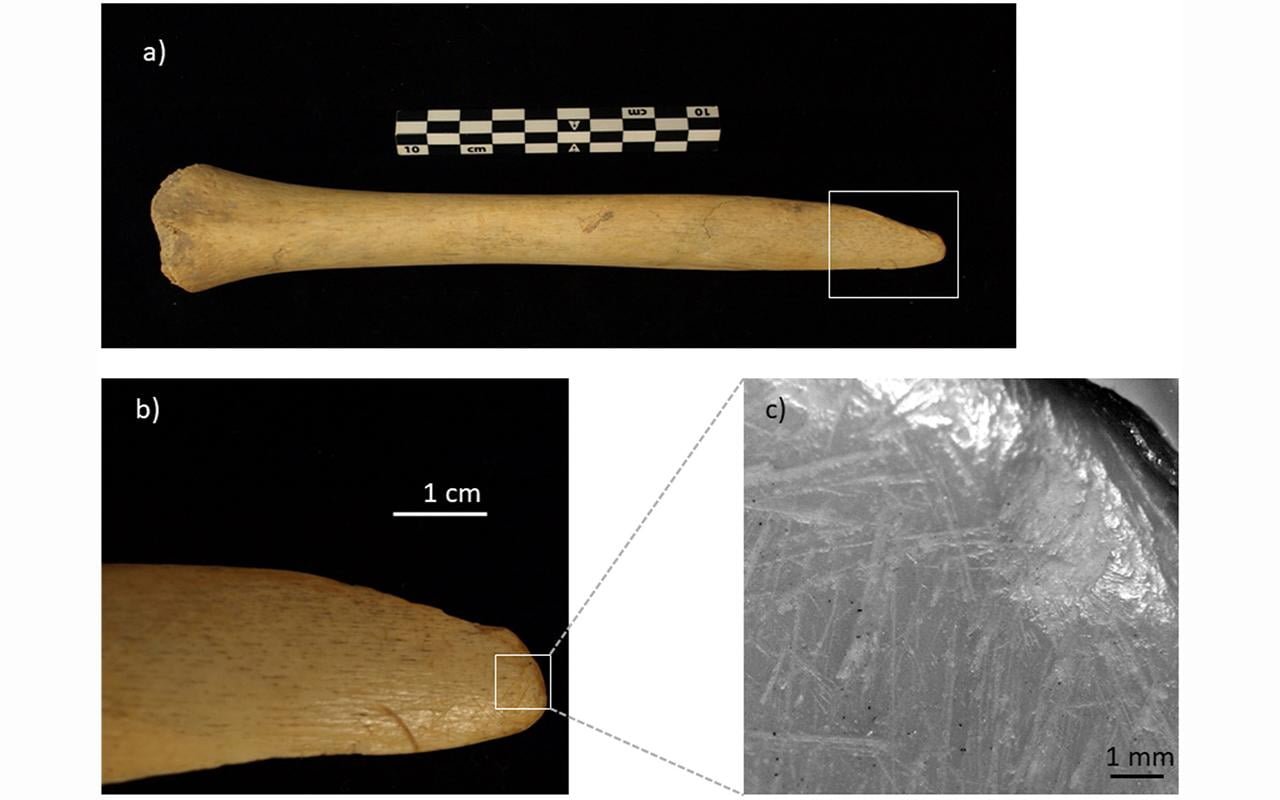

The findings, published in the journal PLOS One, reveal how prehistoric people in the Iberian Peninsula engaged with their deceased, manipulating and repurposing human bones, with potential uses ranging from tools to dinnerware.

The study, conducted by a team of researchers from the University of Bern in Switzerland, the University of Córdoba in Spain, and numerous other experts, centered on the remains found at Cueva de los Marmoles in southern Spain’s Andalusia region.

The cave, located about 45 miles southeast of Córdoba, has long been a significant site for burials, dating back to approximately 6,000 to 3,000 years ago, covering the Neolithic to the Bronze Age periods.

The examination of at least 12 individuals’ remains revealed signs of deliberate bone modifications, suggesting post-mortem actions like fractures and scraping, possibly for marrow extraction or other purposes.

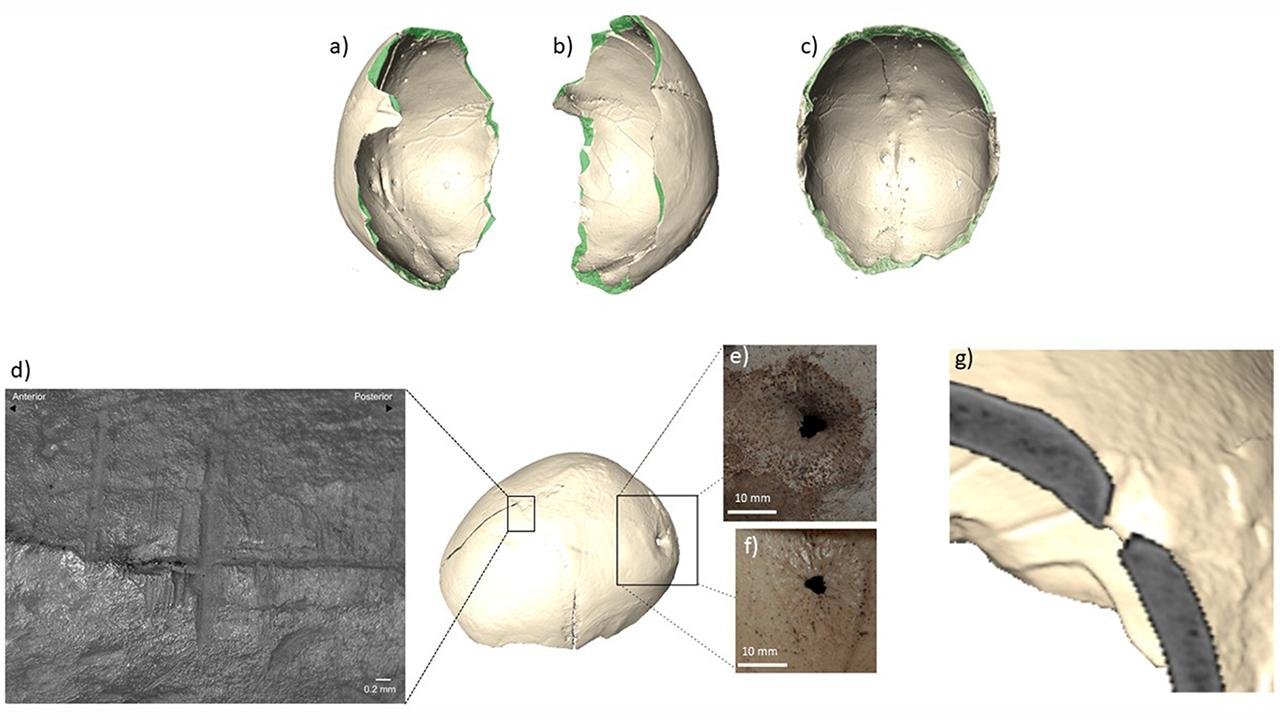

A particularly striking discovery was a “skull cup” crafted from a human cranium, likely that of a man aged 35 to 50. Researchers found evidence of intentional separation of the cranium from the lower skull and extensive scraping to remove flesh. Similar skull cups have been found in other Neolithic sites in southern Spain, hinting at possible diverse functions, including the consumption of brain matter or liquids.

Although the exact motivation behind these practices remains elusive, researchers have proposed several theories. One possibility is that these actions were carried out during funerary services, serving as a way to mediate the transition between the realms of the living and the dead, emphasizing the importance of the deceased in the lives of the living.

Numerous other cave sites across the Iberian Peninsula have shown similar evidence of bone modifications, suggesting shared complex cultural beliefs regarding death and the afterlife. However, the study authors are cautious not to draw definitive conclusions, recognizing that the precise symbolic meanings of these practices require further investigation.

The extensive time frame during which Cueva de los Marmoles was used for these practices is another fascinating aspect. The site was utilized in three distinct phases between approximately 3,800 BCE and 1,300 BCE, with intervals of up to a thousand years between each period. This raises questions about how knowledge of the site was passed down through generations. Oral histories, myths, or traditions could have played a role in guiding people back to the cave for these unique rituals.