The discovery of the largest cluster of sunken vessels from the 18th and 19th centuries in the northern Bahamas sheds new light on the harrowing history of the transatlantic slave trade. Identified as a “highway to horror” by British marine archaeologist Sean Kingsley, these wrecks serve as silent witnesses to the brutal colonial past, carrying enslaved Africans on nightmarish voyages.

A comprehensive research effort led by the Bahamas Lost Ships Project, spearheaded by Allen Exploration, has brought to light the haunting legacy of 14 slave ships that sank between 1767 and 1860. These vessels, mostly American-flagged, were part of a sinister network profiting from the exploitation of human lives in Cuba’s sugar and coffee plantations. Kingsley highlights Cuba’s duplicitous role, ostensibly agreeing to end the slave trade while actively engaging in extensive trafficking.

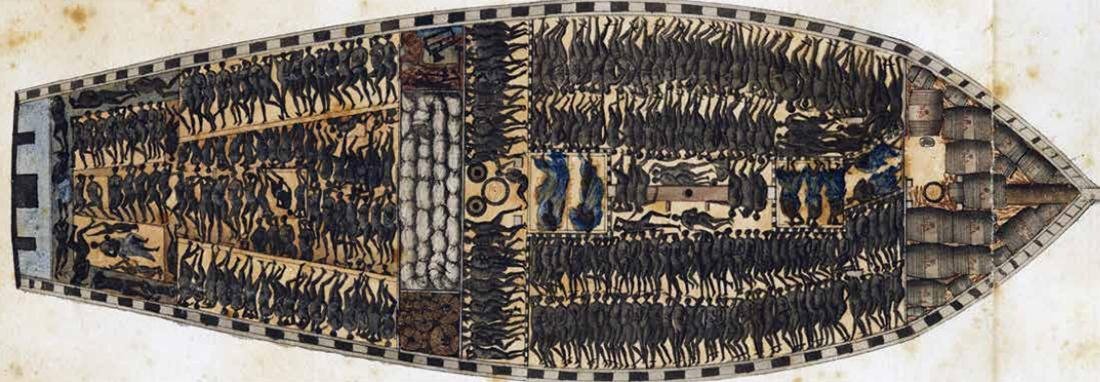

The fate of those trafficked in these ships remains largely unknown, with many forced below deck as the vessels foundered, ensuring the crew’s escape while condemning the enslaved to a watery grave. Kingsley emphasizes the horrors endured by these individuals, forced to confront a new terror in the form of shipwrecks after enduring unimaginable hardships throughout their journey.

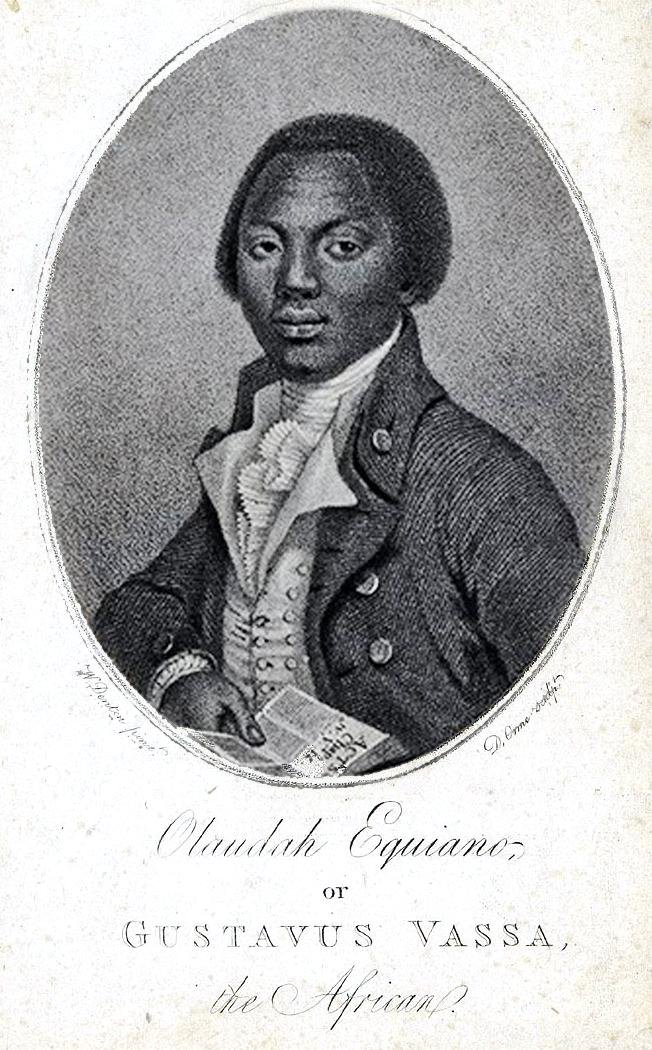

The research, detailed in a report titled “Greater Abaco’s Shipwrecked Echoes of the Caribbean Plantation Economy,” underscores the urgent need to acknowledge and confront this dark chapter of history. Notable among the wrecks is the ship that once carried Olaudah Equiano, a formerly enslaved individual who survived the disaster to become a leading abolitionist voice.

Michael Pateman, director of the Bahamas Maritime Museum, reflects on the horrors faced by those enslaved, particularly in Cuba’s sugar plantations, emphasizing the importance of remembering their suffering. Carl Allen, founder of Allen Exploration, echoes this sentiment, stressing the significance of history and archaeology in preserving and honoring these memories.

Detailed historical documentation reveals the extensive maritime traffic in the region, dating back to at least 1657, with the Providence Channel serving as a crucial passage for ships navigating between the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Florida.

The research also highlights the illegal involvement of US ships in the trafficking and transport of enslaved Africans. Of the 14 ships wrecked in the Greater Abacos region, 11 were US-flagged, underlining the deep entanglement of American vessels in the transatlantic slave trade. Ports of departure ranged from Africa to Virginia and South Carolina in the United States, with final destinations including Cuba, New Orleans, and Nassau.

The report’s publication, coinciding with Black History Month in the US, serves as a timely reminder of the atrocities of the past that must not be forgotten. As Carl Allen aptly puts it, “History and archaeology let us give new life to the memories using physical evidence that nobody can ignore.”