Recent research on skeletal remains from the ancient Egyptian necropolis of Abusir, dating back to the 3rd millennium BCE, has uncovered the occupational hazards faced by scribes due to their repetitive tasks and working postures. This study, published in the journal Scientific Reports, highlights how the daily activities of these literate men led to degenerative changes in their skeletons.

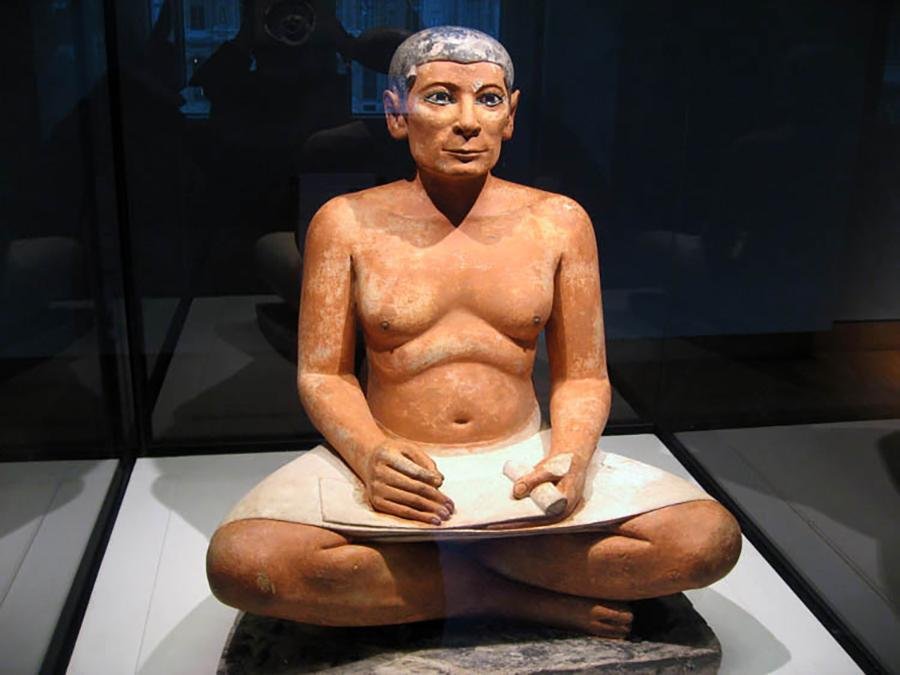

In ancient Egypt, scribes held a prestigious status, primarily due to their literacy—a skill possessed by only about 1% of the population during the Old Kingdom. Scribes performed vital administrative functions and were integral to the operation of the state’s bureaucracy. Despite their high social standing, the physical toll of their work is evident in their skeletal remains.

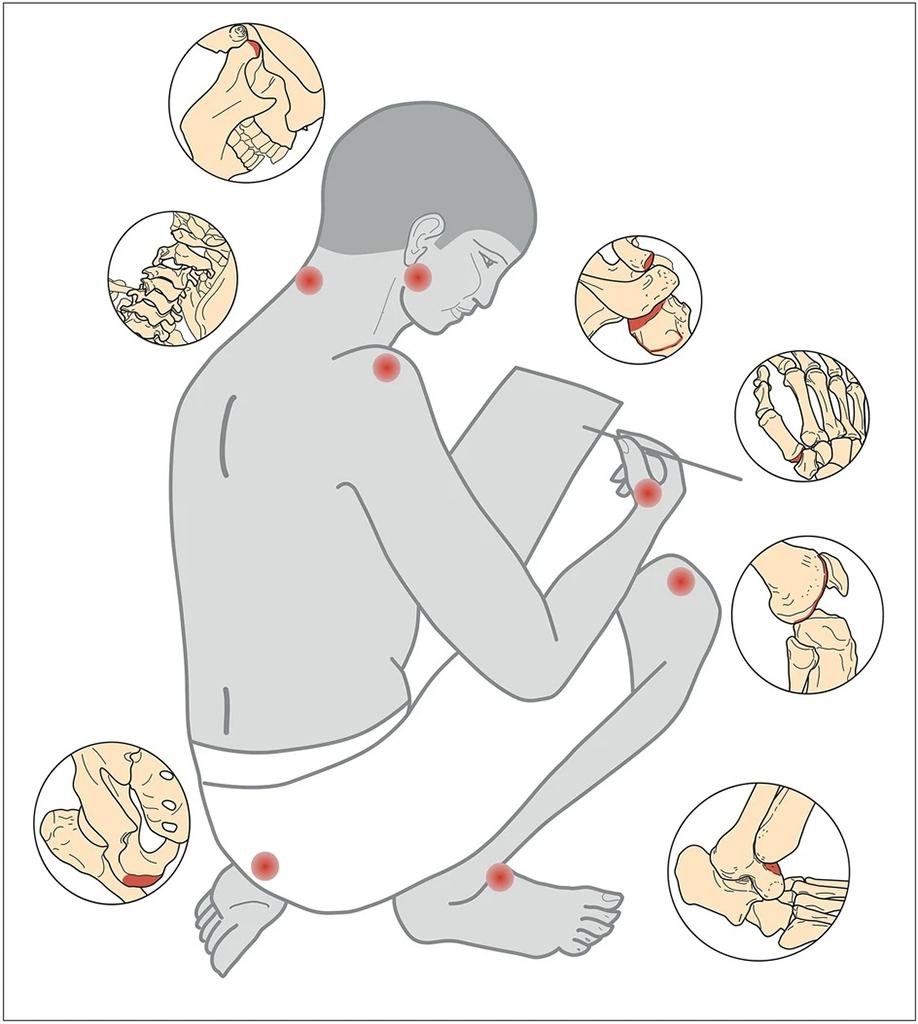

Petra Brukner Havelková, an anthropologist with the National Museum in Prague, led a team that examined the remains of 69 adult males buried in Abusir, 30 of whom were identified as scribes. The researchers found that scribes exhibited a higher prevalence of degenerative joint changes compared to their non-scribe counterparts. These changes were most pronounced in the joints connecting the lower jaw to the skull, the right collarbone, the top of the right humerus, the first metacarpal bone in the right thumb, the bottom of the thigh, and throughout the spine, especially in the neck.

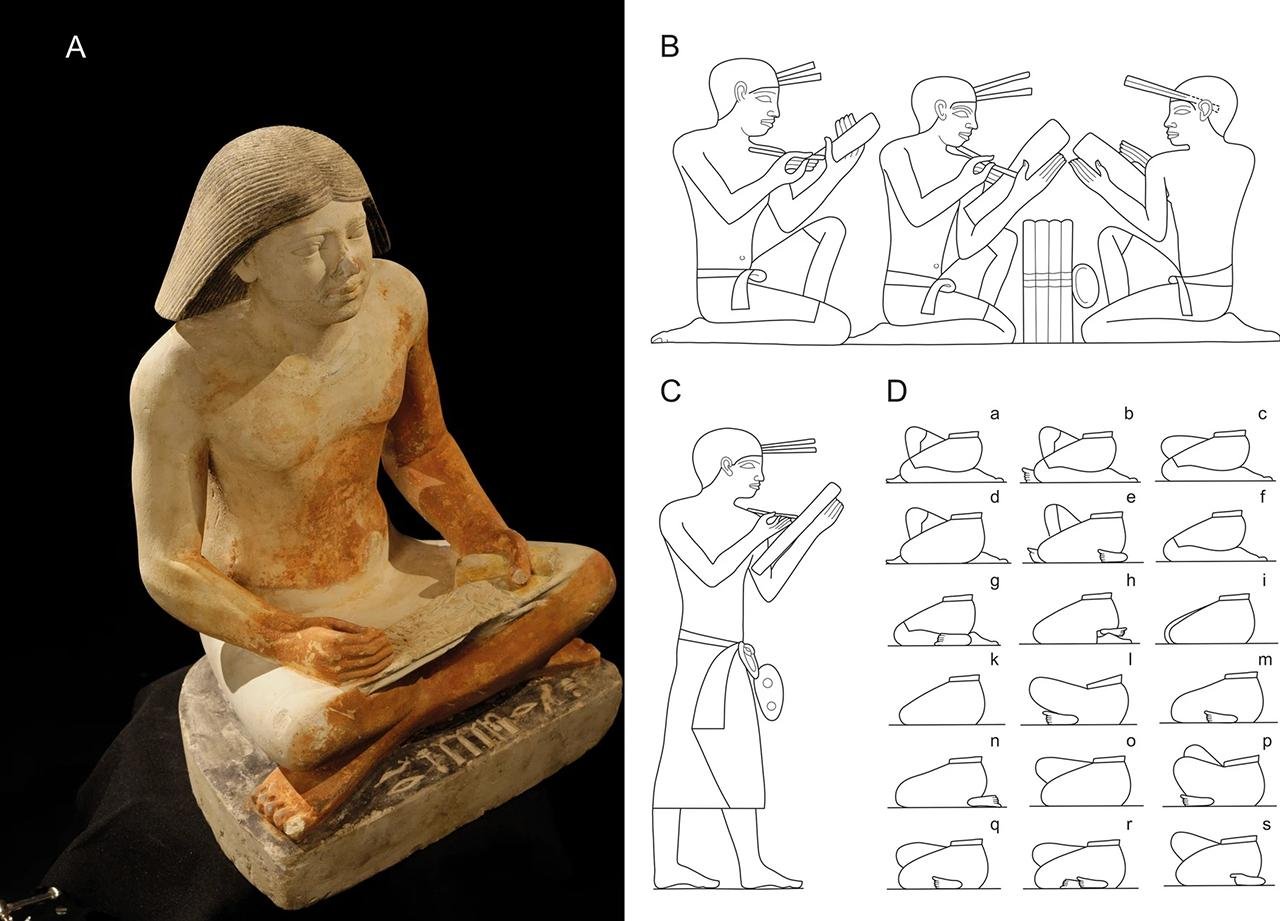

The team suggested that these degenerative changes likely resulted from the prolonged cross-legged sitting position commonly adopted by scribes, with the head bent forward, the spine flexed, and the arms unsupported. Additional changes in the knees, hips, and ankles indicated that scribes might have also sat in a kneeling or squatting position, with one leg bent upwards.

Archaeological evidence, such as statues, wall reliefs, and historical texts, corroborates these findings, depicting scribes in various working postures. These sources reveal that scribes typically used a thin rush pen for writing on papyrus, wooden boards, and ostraca. The physical stress from their repetitive tasks is further evidenced by signs of degeneration in their jaw joints, likely caused by chewing the ends of rush stems to form brush-like heads, and in their right thumbs from pinching the pens.

“Our research reveals that remaining in a cross-legged sitting or kneeling position for extended periods, and the repetitive tasks related to writing and the adjusting of the rush pens during scribal activity, caused the extreme overloading of the jaw, neck, and shoulder regions,” the study authors wrote.

The skeletal changes observed in ancient scribes have parallels in modern occupational health issues. Prolonged sitting in inappropriate positions continues to affect the human skeleton similarly today, causing spine degeneration, joint arthrosis, and subsequent pain. “We can only record changes in the skeleton, not in any soft tissues,” Havelková told Newsweek. “But, according to the results of our study, compared with the results of clinical, orthopedic, and ergonomic studies of current occupational risk factors, it seems that prolonged sitting in an inappropriate position still affects the human skeleton in the same way.”

The study underscores how even privileged positions in historical societies came with their own set of occupational hazards, revealing a more nuanced picture of daily life in ancient Egypt.