Archaeologists have been investigating human bones discovered near the ruins of a bridge in the Three Lakes region of Switzerland. This research aims to unravel the mysteries surrounding these remains and to enhance our understanding of the region’s Celtic heritage.

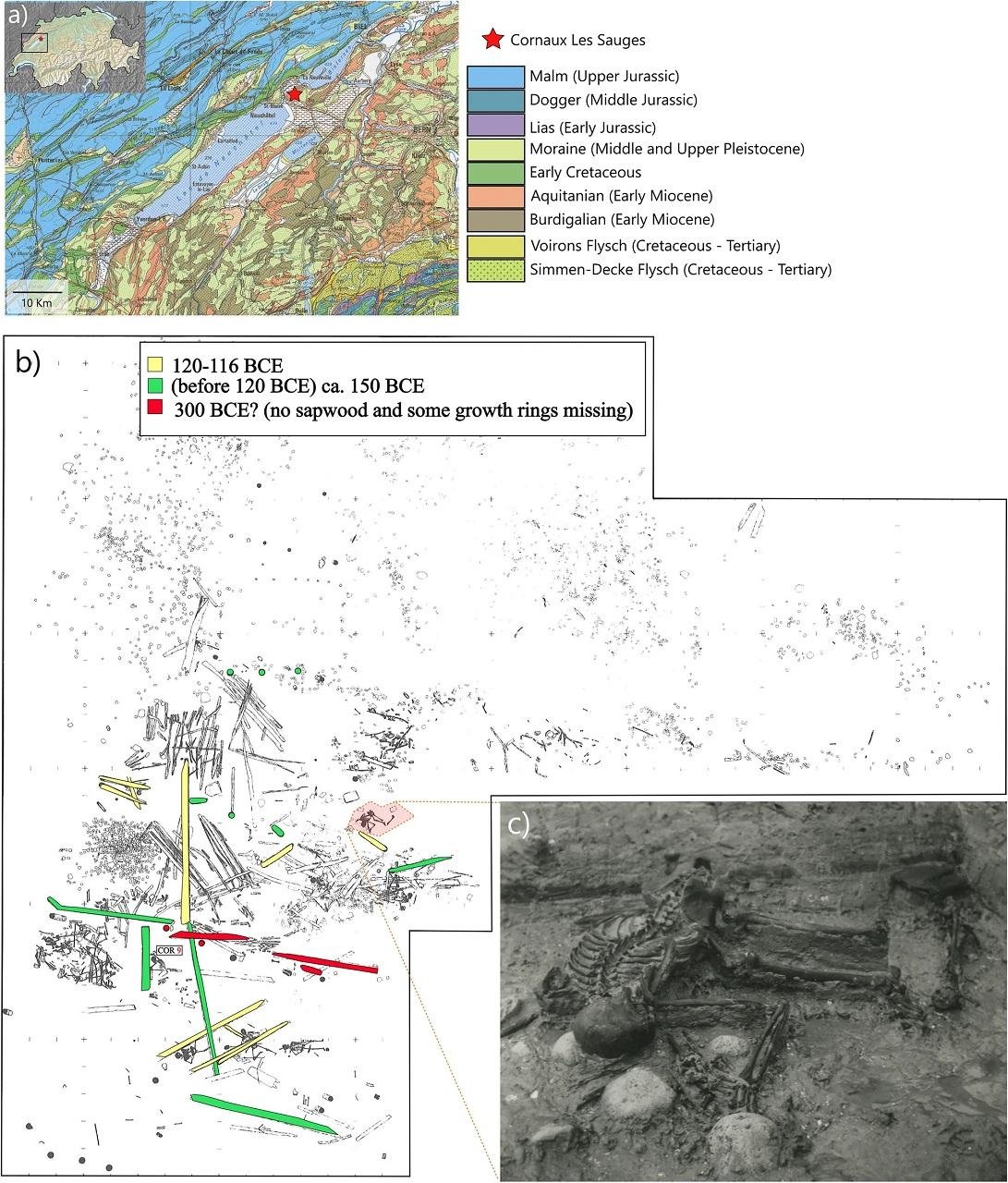

In 1965, renovations of the Thielle Canal led to the discovery of a mix of bones, skulls, and wooden beams on the bed of a river near the ruins of the Celtic bridge at Cornaux/Les Sauges. The site revealed 20 skeletons, prompting decades of speculation and research.

A multidisciplinary team of specialists in archaeology, anthropology, thanatology, biochemistry, and genetics has now revisited this intriguing case. Their findings, supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation and the Autonomous Province of Bolzano, were recently published in the journal Scientific Reports.

This study forms part of an international project led by the University of Bern and the Eurac Research Institute for Mummy Studies in Bolzano. The project aims to improve our understanding of the Celts in Switzerland and Northern Italy. The predominantly oral culture of the Celts has left limited written records, with much of the available information coming from the writings of Julius Caesar. “They are the stories of a military adversary, so they are not necessarily objective and complete,” says Zita Laffranchi, a postdoctoral fellow at the Institute of Forensic Medicine at the University of Bern. By focusing on archaeological finds, researchers hope to give a voice to the people not documented in historical texts.

Laffranchi and her colleagues conducted a bioarchaeological investigation to reconstruct the events at Cornaux/Les Sauges. The ruins of the Celtic bridge and the skeletons are indeed controversial. Some theories suggest that a sudden flood or tsunami caused the collapse of the wooden structure. Others propose that the bodies were victims of human sacrifice, a practice associated with water in Celtic culture.

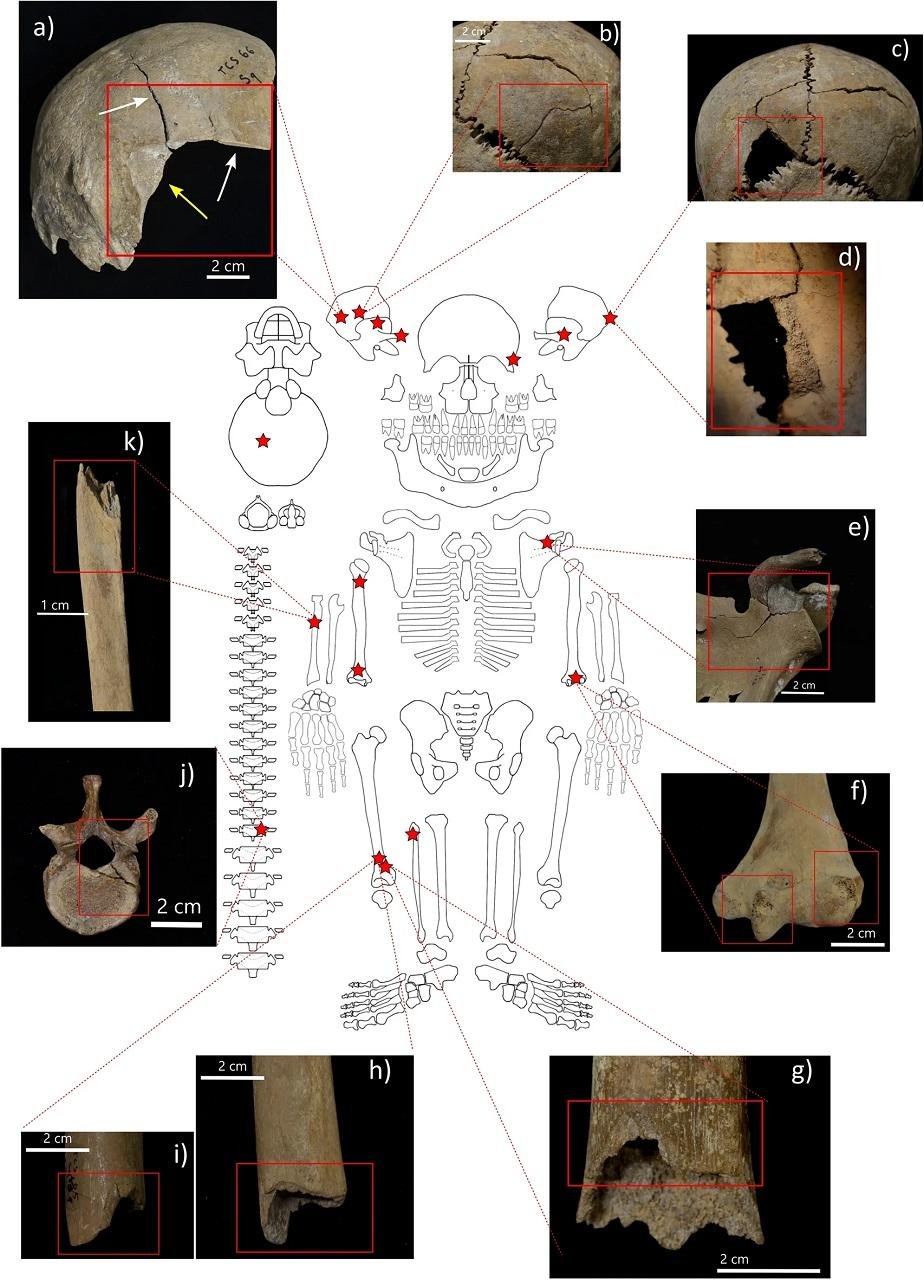

To uncover the truth, the team examined the skeletons from all angles. The state of preservation and the notable presence of brain fragments in five skulls suggest that sediment covered the bodies shortly after death. The remains showed multiple bone injuries distributed throughout the bodies, from skulls to legs, appearing to have been caused by violent impacts. Notably, no injuries consistent with intentional harm or sharp objects were identified, contrasting with findings at other European sites where sacrifices are documented. Additionally, some bones were entangled with wood pieces, pointing to an accidental event. These elements support the theory that a tsunami caused the bridge’s collapse.

Beyond the skeletal remains, chemical analyses of the bones and teeth have provided valuable information. Radiocarbon dating has helped establish a timeframe for when these individuals lived, while isotopic analyses have shed light on their diets and places of residence. Remarkably, paleogenetic analyses have allowed researchers to analyze the ancient DNA of half of the individuals found. Through these scientific techniques, scientists confirmed the presence of at least 20 people, including a young girl, two other children, and 17 adults, most of whom were young men.

This demographic bias towards young adult males could indicate a group of prisoners, slaves, merchants, or soldiers. However, some ambiguity remains regarding the timing of their deaths. While some radiocarbon dates suggest they may have perished during the destruction of the bridge, it is impossible to definitively confirm that all the deaths occurred simultaneously and coincided with that event.

“Considering all these elements, it is very likely that a violent and sudden accident took place in Cornaux,” summarizes Marco Milella, a researcher at the University of Bern and co-leader of this project. “But this bridge had a prior life. It may have been a place of sacrifice, and it is conceivable that some corpses preceded the accident. There is no reason to choose between the two alternatives.”

The exact sequence of events at the Celtic bridge in Cornaux/Les Sauges is likely to remain a mystery. “In this type of research, we are interested in individuals. We trace their life stories, which can be emotional,” says Laffranchi. “But at its root, the goal is to better understand our cultural and biological heritage, at the level of the population.”

The Three Lakes region held significant importance for the Celts, particularly the Helvetii, the largest Celtic tribe that settled between Lake Geneva and Lake Constance. This new study, the first to utilize paleogenomics to analyze Celtic individuals from Switzerland, confirms their genetic proximity to other Iron Age populations. Notably, some lineages identified in Cornaux have also been found in Britain, the Czech Republic, Spain, and central Italy. Isotopic analyses indicate that while some individuals may have grown up in the Three Lakes region, others originated from the Alps.

Swiss National Science Foundation