Excavations at the historic Blackberry Hill Hospital site in Stapleton, Bristol, have unearthed significant remains, shedding light on the challenging lives of those who lived, suffered, and died there over the centuries.

Led by Cotswold Archaeology between 2018 and 2023, this work, funded by Vistry Group, began as a precondition to the site’s redevelopment for housing but has since revealed invaluable information about the city’s past.

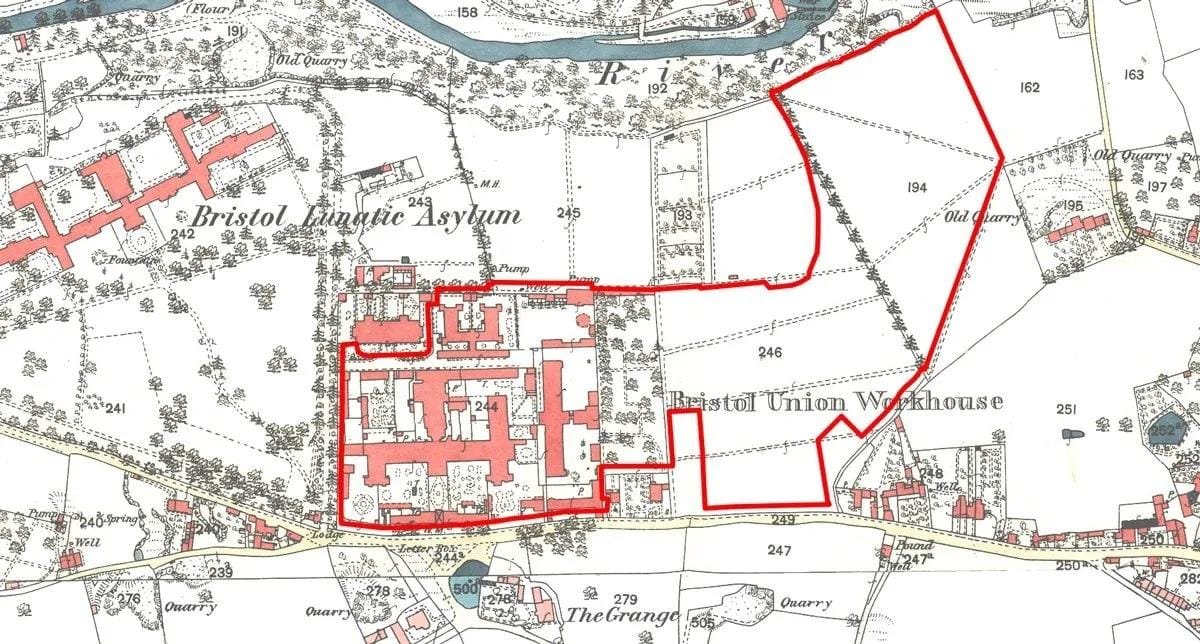

The site’s complex history spans multiple roles, from Stapleton Prison to Stapleton Workhouse, and later as Blackberry Hill Hospital. Initially established in the late 18th century, the area served as a prisoner-of-war camp, known as Stapleton Prison, primarily housing captured sailors from Britain’s wars with France, Spain, Holland, and the United States.

As Richard Leaman, Diocesan Secretary of the Diocese of Bristol, explained, the historical significance of Stapleton as “one of the earliest examples of a prisoner-of-war camp in Britain” precedes even the Norman Cross camp. The prison era ended with the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars, after which the site transitioned through various roles amid Britain’s evolving social challenges.

In 1832, amidst a devastating cholera outbreak across the United Kingdom, the prison was repurposed into a hospital in an attempt to contain the spread of the disease, which claimed over 50,000 lives. This initial healthcare function was short-lived, however, as in 1837 the facility transformed again into the Stapleton Workhouse, intended to shelter Bristol’s impoverished. While the workhouse was theoretically a place of refuge, the reality was often harsh.

According to Cotswold Archaeology, many who found themselves in the workhouse endured extreme poverty, neglect, and hardship. These institutions, often overcrowded and marked by poor conditions, inspired Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist, depicting the systemic struggles faced by the vulnerable of Victorian society.

The excavation team uncovered over 4,500 unmarked graves, the majority from the workhouse period, providing a stark reminder of Bristol’s darker past. These remains, discovered with respect under a Burial Licence from the Ministry of Justice and a Faculty from the Diocese of Bristol, represent the lives of countless individuals who lived in deprivation. Richard Leaman described the project’s handling of these remains as “reverential and lawful,” emphasizing the effort to honor the site’s past. A marker will memorialize the graves, and a final ceremony will accompany the reburials.

Ongoing studies of select remains aim to deepen understanding of life, health, and mortality in 19th-century Bristol. Researchers are analyzing the remains alongside personal items found in the graves, piecing together stories that reflect the challenges faced by the poor and sick of Victorian-era Bristol. The study also hopes to confirm whether any of the burials belong to prisoners from the site’s earlier prison era.

Blackberry Hill’s layered history, spanning over two centuries, makes it a significant archaeological site that chronicles the evolution of public health, social welfare, and incarceration in Bristol. The excavation is ongoing, with results expected to be published by Cotswold Archaeology in 2026.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.

It would be interesting if DNA testing could be done on a group of remains to find out where these people were from and where their ancestors moved to.

I thought it was kind of rude not to mention Josh Gates name in regards to the Petra story. Josh is proud of bringing these subjects to the world. And his excitement is shared by all who are on these discoveries.