The Incas, renowned for their vast empire and sophisticated culture, controlled their expansive territory through a strategic combination of military dominance and religious authority. Central to their rituals was the use of ceramics, which not only served practical purposes but also embodied their ideological and imperial values. Among these rituals, the capacocha ceremony, a poignant and solemn act of child sacrifice performed on mountain peaks, stands out as a testament to their religious devotion and imperial control.

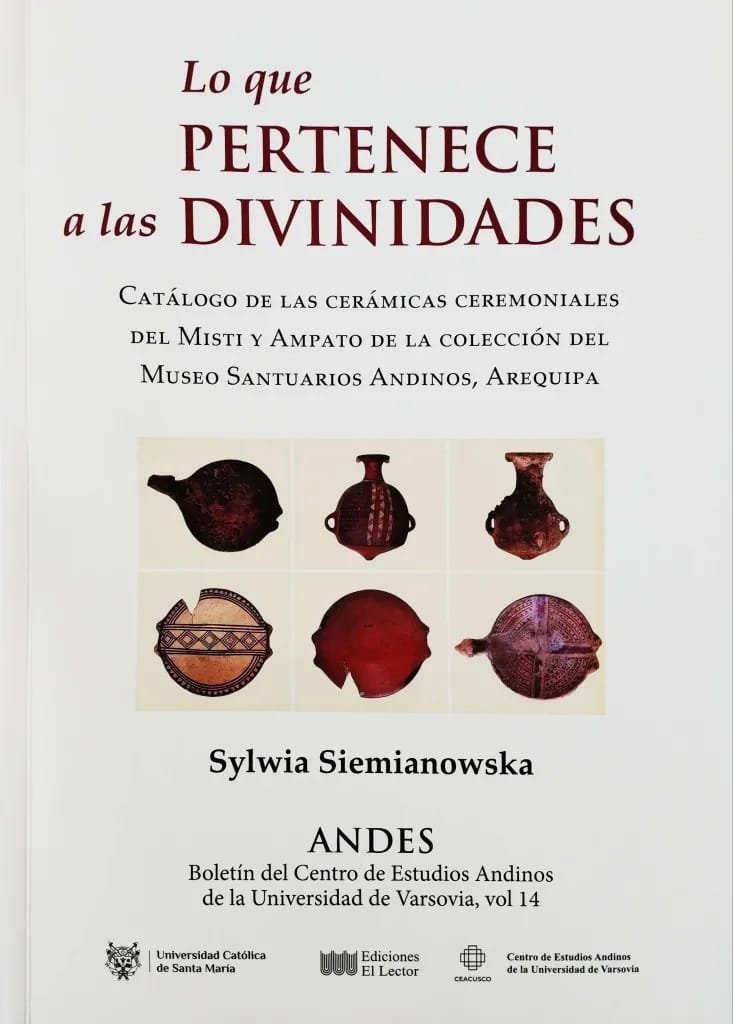

Dr. Sylwia Siemianowska of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology of the Polish Academy of Sciences (IAE PAN) has extensively studied these ceremonies. In her recently published bilingual book, Lo que pertenece a las divinidades, she catalogues Inca ceramics discovered alongside child sacrifices on Peru’s Misti and Ampato volcanoes. The capacocha ritual, practiced approximately 500 years ago, involved the sacrifice of children aged 6 to 13, who were considered divine messengers carrying offerings and prayers to the gods.

Dr. Siemianowska explains that ceramic vessels played a vital role in Inca burial and ritual practices. These vessels were not mere objects but symbols of the empire’s religious and political ideologies. Found alongside sacrificial remains on Misti and Ampato, the ceramics included puccu plates, bowls, and the iconic Inca aryballos—amphorae used to store ceremonial chicha, a fermented maize drink central to many Inca rituals. “It is a kind of gift for a deity,” she noted in an interview with PAP, describing how, during sun ceremonies, the Inca would drink chicha from one cup and offer it to the Sun from another, symbolizing a connection between the mortal and divine realms.

Research conducted in 2020 by Dagmara Socha of the Andean Research Center at the University of Warsaw uncovered significant finds on Misti and Ampato. On Misti, eight to nine children were buried with grave goods that included 47 figurines made of gold, silver, and copper, stone vessels, Spondylus shell artifacts, and 32 ceramic vessels. Similarly, on Ampato, three child graves, including a six-year-old boy and two girls, were accompanied by 37 ceramic vessels, along with other artifacts.

These artifacts now reside in the Museo Santuarios Andinos in Arequipa, Peru. The ceramics are adorned with geometric patterns, wavy lines, and zigzags painted with mineral pigments after firing. While most of the vessels were intact, some on Ampato appeared to have been deliberately broken, a ritual act thought to seal the sacred space.

The Incas’ use of ceramics extended beyond practical functions. These objects served as powerful symbols of Inca imperialism, reflected in their standardized forms, decorations, and materials. “Ceramics carried ideas, symbolized belonging to a specific social group, and marked norms and customs,” explained Dr. Siemianowska. Ritual ceramics, especially miniature vessels, were crafted exclusively for ceremonial purposes and lacked utilitarian functions.

One unique aspect was the use of well-sealed vessels for substitute offerings, where materials like llama blood and powdered Spondylus shell were mixed and ceremonially offered to volcanoes. “Since we cannot reach the center of the volcano directly, we make a symbolic offering through a vessel filled with gifts,” noted Dr. Siemianowska.

These discoveries illuminate the intricate connections between Inca religion, politics, and daily life, showcasing the central role of ceramics in sustaining their empire.

Sources: PAP