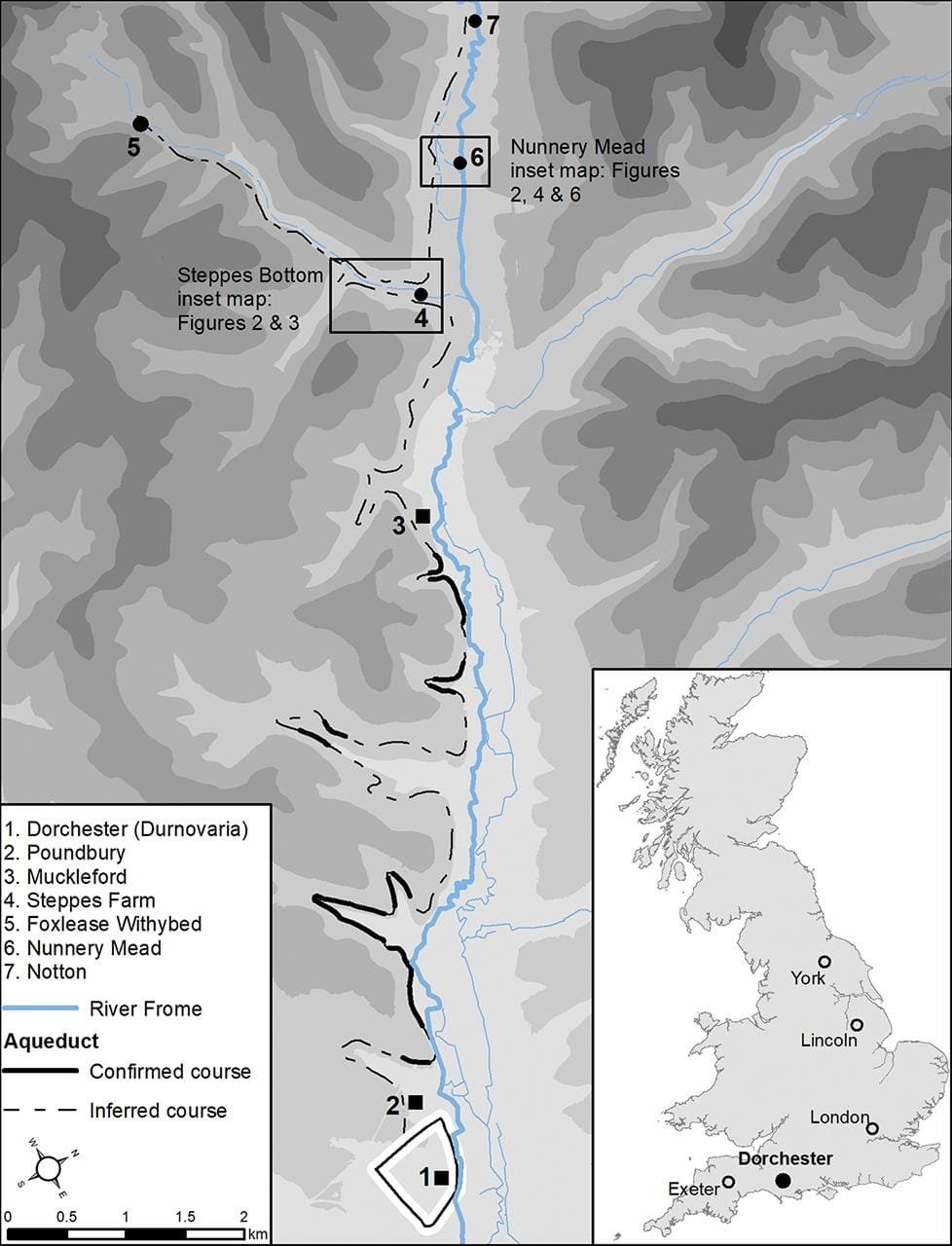

Archaeologists from Bournemouth University (BU) have made a groundbreaking discovery regarding the Dorchester Aqueduct, one of the longest and most extensively studied Roman watercourses in Britain. Their research has revealed that the aqueduct, which supplied fresh water to the Roman town of Durnovaria (modern Dorchester), extended two kilometers further than previously thought, reaching the village of Notton on the River Frome.

The Dorchester Aqueduct, known for its critical role in providing water to public baths, fountains, and affluent households in Roman Britain, represents a vital element of Roman urban infrastructure. Harry Manley, from BU’s Department of Life & Environmental Sciences, said: “Getting water supplied into prominent structures and buildings in the town would have been a sign of modern living at the time, and an indicator of the town’s status.”

The research team employed innovative methods to map the previously unknown sections of the aqueduct. Utilizing publicly available LiDAR data, which analyzes land elevation and features, Manley traced the aqueduct’s route upstream from the previously believed water source at Steppes Bottom lake. This analysis, corroborated by a geophysical survey conducted near Frampton Villa, revealed evidence of a narrow channel running northwest to southeast. Ground-penetrating radar surveys and subsequent excavations further confirmed the presence of a wooden aqueduct channel at these locations.

The excavation uncovered remnants of decomposed wooden planks that once formed a rectangular, box-shaped conduit approximately one meter wide and 0.35 meters deep. This evidence highlights the engineering ingenuity of Roman Britain, which, while simpler in design compared to aqueducts in continental Europe, was nevertheless a source of civic pride and practicality.

Previous studies had suggested that the aqueduct originated at Steppes Bottom. However, the new findings indicate that its source was likely further upstream, near Notton. This discovery challenges earlier interpretations, such as those by Bill Putnam, whose 1990s excavations identified features in Steppes Bottom potentially associated with water management for a medieval priory. The new data suggests these features could instead be remnants of Roman engineering designed to carry water across the valley.

The findings, published in the journal Britannia, provide a clearer picture of the aqueduct’s construction and maintenance. Integrating archaeological evidence from the past century with modern topographic data, the team is developing a comprehensive analysis of the aqueduct’s full 20-kilometer route. This effort is bolstered by access to previously unpublished archival data from Putnam’s original excavations. “This research has clearly shown the benefit of integrating archival archaeological evidence with landscape-scale topographic data within a GIS,” the researchers stated.

The discovery underscores the importance of the aqueduct not just as a functional water supply system but also as a symbol of Roman innovation and urbanization in Britain. It adds a critical chapter to the history of Durnovaria, a town that played a strategically significant role during the Roman occupation. As Manley explained, “Understanding more about how it was constructed and maintained, and where it began, adds further detail to this vital aspect of Roman life.”