Archaeologists have uncovered evidence of a unique ritual sacrifice involving close family members in the ancient Moche culture of Peru. Genetic analysis of six individuals buried in a 1,500-year-old tomb at Huaca Cao Viejo, part of the El Brujo archaeological complex, reveals that two adolescents were sacrificed to their close relatives during funerary rites for high-status individuals.

The Moche civilization thrived along Peru’s northern coast between 300 and 950 CE, known for its elaborate social hierarchy and ceremonial human sacrifices to deities. However, the recent discovery marks the first documented instance of sacrifices involving adolescent relatives during funerary ceremonies. “Most of what we know about human sacrifices with the Moche relates to very public and gruesome forms of human sacrifice,” said Lars Fehren-Schmitz, an archaeogeneticist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, in a statement to Live Science. “No evidence has pointed to the sacrifice of close or adolescent relatives like we observed.”

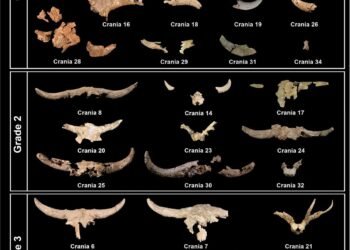

The burial site, discovered in 2005, held the remains of six individuals, including the well-preserved body of a high-status woman known as Señora de Cao. Alongside her were three men and two adolescents, a boy and a girl, who had been strangled with plant fiber ropes. Genetic analysis confirmed that the two teenagers were closely related to the adults buried in the tomb. The boy is believed to have been sacrificed following his father’s death, while the girl appears to have been offered during her aunt’s burial.

“This study provides the first confirmation of familial relationships within an elite Moche burial group from Huaca Cao Viejo, offering new insights into Moche social organization, burial practices, and kinship-based politics,” the researchers wrote. Using genomic sequencing, the team reconstructed a family tree spanning at least four generations. Señora de Cao was identified as the probable aunt of the sacrificed girl, while one of the men was likely the father of the girl and the brother of Señora de Cao. Another man buried in the tomb, who had died decades earlier, may have been the siblings’ father or grandfather.

While sacrifices were a common practice in Moche culture, these findings suggest a previously undocumented form of ritual that was more private and perhaps reserved for high-status individuals. “The idea is that this is a more private and dignified form of ritual killing probably reserved for individuals of higher societal or religious/spiritual status,” Fehren-Schmitz explained.

Isotopic analysis provided additional context, revealing that most individuals buried in the tomb had diets rich in maize and animal protein and spent their childhoods near the Chicama Valley. However, the sacrificed girl showed evidence of a distinct diet and geographic origin, indicating she may have been raised far from her parental home.

This discovery underscores the central role of kinship in Moche society, not only in transmitting status and authority but also in their ceremonial practices. By linking the living and the deceased through familial sacrifices, the Moche reinforced their connection to both ancestors and the divine.

The findings were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).