Archaeologists in Israel have made revolutionary discoveries that question previous long-held assumptions about religious asceticism in the Byzantine period. Recently, excavations at the Khirbat el-Masani monastery, northwest of Jerusalem, revealed the remains of an individual wrapped in heavy metal chains. Generally, this was a theme associated with male ascetics, but scientific analyses revealed a surprising truth: the remains belonged to a woman.

The excavation by the Israel Antiquities Authority and researchers from the Weizmann Institute of Science uncovered a number of burial crypts dating between the 4th and 7th centuries CE. Among these, one burial stood out. Though the skeleton was poorly preserved, extreme asceticism was signaled by the presence of chains—an intense religious practice in which devotees renounced worldly comforts to achieve spiritual purity. Traditionally, such self-imposed suffering, including bodily restraints and self-mortification, has been associated with male monks.

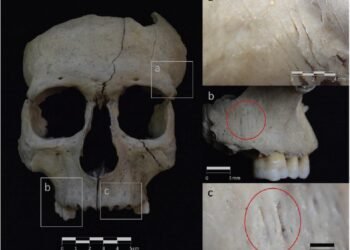

The poor condition of the bones proved inadequate for conventional osteological approaches to determining the sex of the skeleton, which forced the researchers to use an innovative technique known as dental enamel proteomics. Upon examining peptides within the enamel of a single tooth, they identified the presence of AMELX, a protein encoded on the X chromosome, and the absence of AMELY, which is present only in males. This conclusively indicated that the individual was female.

The significance of this discovery is highlighted in a study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. According to the researchers, the evidence of a female ascetic practicing such extreme bodily penance is unprecedented in the archaeological record.

Asceticism became an important phenomenon in early Christianity, especially following the year 380 CE when Christianity became the dominant faith of the Roman Empire. Monasticism flourished, and practitioners sought ways to discipline the body to strengthen the soul. While some monks lived atop pillars for years, others wore chains or engaged in prolonged fasting and isolation.

Although historical sources confirm the existence of female ascetics, including Melania the Younger, a noblewoman who lived in seclusion for prayer and fasting, there had, until this discovery, been no similar material evidence to suggest women participated in the most extreme forms of bodily self-mortification. This discovery thus fundamentally changes the perception of women’s role in this ascetic community and raises questions about the extent of their participation in rigorous monastic traditions.

The Khirbat el-Masani monastery was built along a pilgrimage route to Jerusalem, which became a major religious center during the Byzantine period. Not only did this monastery serve as a place of worship and learning, but it also acted as a residence for pilgrims who came from afar to the Holy City. The presence of a female ascetic here may suggest that women actively and rigorously participated in monastic life.

Archaeologists believe this discovery challenges previously held beliefs about gender roles in early Christian monasticism. While asceticism among women was known, the identification of a female practitioner of extreme bodily mortification shifts the narrative.

The researchers plan to investigate other Byzantine monastic sites to determine whether more such cases exist.