More than a decade ago, after three decades of searching, metal detectorists Reg Mead and Richard Miles uncovered one of the biggest Celtic hoards ever found. The Le Câtillon II hoard contained about 70,000 silver coins, gold torques, and jewelry, all found in Jersey’s Grouville parish. Despite copious research, one main question remained unanswered until now: Why was such an immense treasure buried in an isolated location, far from known Celtic settlements and trade routes?

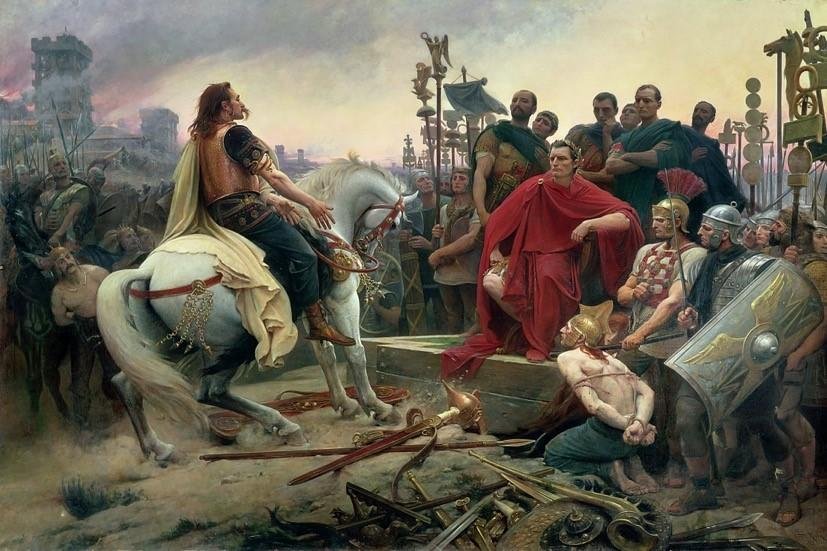

A recent study in Wreckwatch magazine presents new theories that challenge previous assumptions about the origins and purpose of the Le Câtillon II hoard. According to the latest findings, this extraordinary cache belonged to the Coriosolitae, a Celtic tribe from northeastern Brittany. It had probably been brought to Jersey amid the turmoil of the mid-1st century BCE during the Gallic Wars when the Roman Empire’s expansion threatened the autonomy of Celtic Gaul. Written sources from 57 BCE describe the Coriosolitae as part of a last-ditch alliance against Rome. The hoard may have made its way to Jersey as a desperate act of preservation after their defeat.

The concept of Jersey as an isolated backwater has gained prominence, but it’s currently being reconsidered. Dr. Phil de Jersey, an expert in Celtic coinage, said: “Jersey was presumably seen as a safe refuge, or at least a slightly safer refuge than trying to hide all these valuables on mainland Armorica.”

Further analysis by Wreckwatch reveals that Grouville was far from a desolate area. The region had a natural anchorage suitable for maritime activity, and historical records suggest that Jersey played a strategic role for England in disrupting French trade and military movements. Dr. Sean Kingsley, editor-in-chief of Wreckwatch, states, “Local sailing families knew very well how to navigate the rocks and shallows. The Coriosolitae wealth, similarly, wasn’t shipped here just for secrecy.”

Richard Miles also disputes the assumption that Jersey was uninhabited at the time. He draws comparisons to Normandy’s archaeological record, which reveals densely spaced Celtic settlements. “Jersey was probably a landscape dotted with little farmsteads,” he suggests. The discovery of single coins in upland areas indicates that coinage was in circulation, likely used in daily transactions among small communities.

Another emerging theory considers the spiritual significance of the hoard’s location. Reg Mead highlights the natural defenses of Grouville, describing how high tides and earthworks may have served as protective barriers. Additionally, Dr. Hervé Duval-Gatignol of the Société Jersiaise proposes that Le Câtillon might have been a sacred site. “This location was not chosen randomly or in the middle of nowhere,” he asserts. “Hoards of this type were often deposited in Celtic temples, and this possibility here cannot be ruled out.” The fear of divine retribution could explain why the treasure was never recovered by those who buried it.

Using advanced geophysical techniques such as magnetometry and electromagnetometry, researchers conducted the largest geophysical survey ever undertaken in the Channel Islands. Their findings reveal linear anomalies resembling Late Iron Age settlements found in northern France. These discoveries support the hypothesis that the hoard was placed in an area of existing human activity, possibly within a ritual or religious setting.

The hoard of Le Câtillon II is one of the most exceptional finds made in Europe. With nearly 70,000 coins, it is by far the largest single deposit of Armorican currency. According to Dr. Phil de Jersey, over 94 percent of the coins are attributed to the Coriosolitae tribe, while the rest are from more than 20 other tribal groups, including the Osismii of central Brittany and the Durotriges of southern England.

Artifacts beyond coins include 23 gold staters, up to 13 gold torques, glass and bone beads, silver ingots, a brooch, and even a Late Bronze Age spearhead dating from 950–800 BCE. All this information helps construct a picture of the cultural and economic interactions between Iron Age societies in Western Europe.

Housed in the La Hougue Bie Museum, the hoard is nevertheless a focus of unwanted attention. “The area is legally protected as a grade one archaeological site, but that’s not always a deterrent,” Richard Miles said. It is always possible for trespassing metal detectorists to continue their work.

The recent findings raise plenty of questions, one of them: Was Le Câtillon a hidden royal mint? A temple offering? Or a last, desperate act to protect tribal wealth? Additional excavations could offer some clarity. As Dr. Kingsley concludes, “There’s something incredibly special about these fields. The spiritual power of the ancestors is likely to have been a big reason why the hoard was brought to Jersey.”

The recent findings raise plenty of questions, one of them being: Was Le Câtillon a hidden royal mint? A temple offering? Or a last, desperate act to protect tribal wealth? Additional excavations could offer some clarity. As Dr. Kingsley concludes, “There’s something incredibly special about these fields. The spiritual power of the ancestors is likely to have been a big reason why the hoard was brought to Jersey.”

For those interested in a deeper exploration of this historic discovery, Wreckwatch magazine offers a special issue, supported by the Highlands College Foundation. Additionally, a documentary on the hoard’s significance is streaming on Wreckwatch TV on YouTube.