A new study published in the European Journal of Archaeology, led by Dr. Astrid Noterman, clarifies the little-known early medieval European burial ritual of bed burials.

The practice, where deceased individuals were interred on or with beds, spanned the sixth to the early tenth century CE and was found in Germany, England, and Scandinavia. The research overturns earlier presumptions that had considered bed burials to be a single tradition; rather, it demonstrates that they were a complex, varied practice that evolved in different regions and social contexts.

Dr. Noterman’s research is among the most comprehensive studies to date, examining not only the actual beds but also their location, surrounding artifacts, and the identity of the individuals interred with them. “This plurality is not limited to regions or time but can also be found within the cemeteries themselves,” she writes. “It therefore seems necessary to shift the focus of research on bed burials away from a single category and start talking about practices, in the plural.”

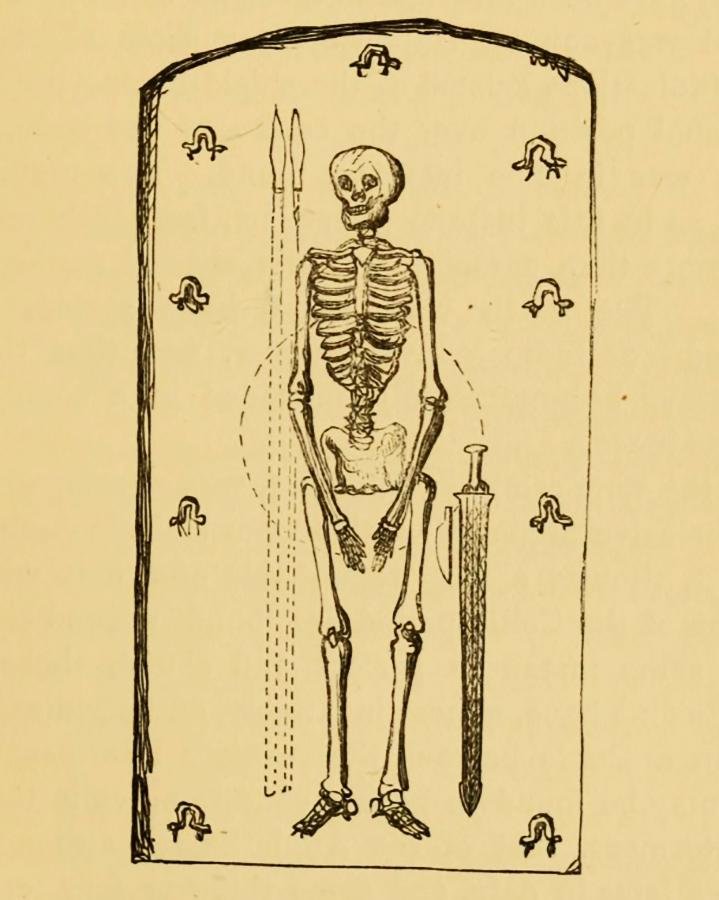

Bed burials in Germany typically took place in unremarkable cemeteries, without any features such as consistent grave orientation. The graves typically had simple wooden bed frames and relatively modest grave goods, such as rings or wooden bowls. Some burials were more elaborate, however, including such items as lyres, candelabras, or even double chairs. Women were frequently buried with weaving tools—spindle whorls, weaving battens, and wooden distaffs—a symbolic link between domestic roles and burial ritual.

England is another story. English bed burials often involve beds that had been dismantled and were sometimes placed inside ancient burial mounds, which were being reused long after they had originally been constructed. Although most of those buried in this way were female, one male example is known from Lapwing Hill in Derbyshire. Stable isotope analysis revealed that individuals buried at locations like Trumpington and Edix Hill had not grown up locally, and that bed burial may thus have been introduced into Britain by continental migrants.

Scandinavian examples, particularly the magnificent ship burials of Oseberg and Gokstad, are different from both English and Germanic traditions. These graves, often placed near waterways so that they would be visible, contained wealthy grave goods and displayed status and power. The two women buried at Oseberg, for instance, were found to have originated from the Black Sea region—again reflecting cross-cultural contacts in burial practices.

The study also draws on emerging fields of research, such as the “archaeology of affect,” suggesting that bed burials would have conveyed emotional and symbolic messages to the living. Beds, Dr. Noterman notes, were also present at all of the major life stages—birth, illness, marriage, and death. Their presence in graves may have been not just practical or symbolic but a means of communication, especially in Christian or elite Scandinavian contexts.

This study promotes a more subtle consideration of medieval burial rites, prompting scholars to consider bed burials not as a single unified rite but as varied practices shaped by regional, social, and emotional factors.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.