An amazing panel of ancient petroglyphs along the coast of Oahu, Hawaii, has again been revealed by the seasonal receding of ocean sands. Etched into sandstone on the Waianae coast, this group of 26 figures—mostly human-like stick figures—has emerged for the first time since 2016, when visitors initially rediscovered them at a nearby military recreation center.

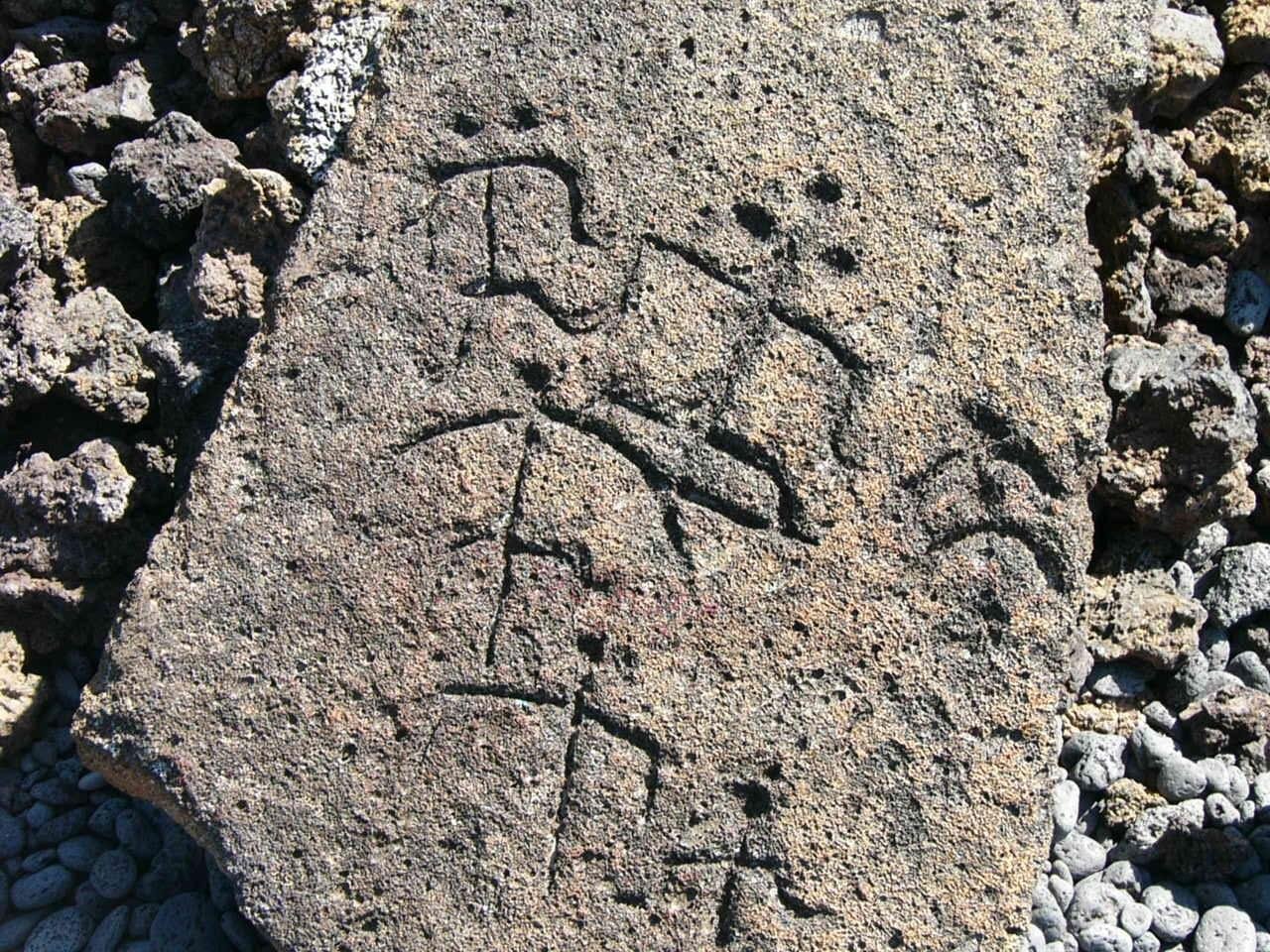

These carvings are visible during low tide, as waves gently roll over rocks covered in algae. Experts date them to be at least 500 to 600 years old, although some of the oral traditions state that Native Hawaiians have been in the area for more than 1,000 years. Carved into a sandstone platform, the petroglyphs extend about 115 feet along the shoreline and include abstract shapes and anthropomorphic human figures, some of which are detailed—two of the large figures even have fingers, a rarity in Hawaiian petroglyphs. The tallest figure is more than eight feet tall.

This reemergence is connected to patterns of seasonal weather. From May to November, Pacific storms churn the waters, scouring sand from beaches and occasionally bringing archaeological features that were obscured by sediment into view. Over time, the sand will eventually return, burying the carvings until they reappear during a shift in coastal dynamics once again.

Specialists monitor the petroglyph site, which lies within the grounds of a U.S. Army recreation area. The shoreline itself is open to the public, but complete access to the adjacent property requires military identification. This has created ongoing controversy about how to preserve this part of Hawaii’s cultural heritage and make it more widely available.

To the Native Hawaiian community, the petroglyphs are not just historic artifacts—they are spiritual and ancestral messages. Some researchers believe they depict ceremonial or religious narratives. One figure with raised and lowered arms might represent sunrise and sunset, connecting the images to natural cycles significant in traditional Hawaiian belief.

The discovery has also prompted reflections on the region’s history. The land where the petroglyphs lie was once home to Native Hawaiian families before being seized for military use in the early 20th century. Some residents resisted displacement, with families exchanging inland lands to remain near their ancestral coastal homes. The location of the petroglyphs along the seawall at the edge of the military area continues to represent a boundary separating the island’s past and its modern uses.

While archaeologists and the Army work to protect the site, they realize too that nature will ultimately reclaim it. As sand shifts and tides rise, the carvings will be lost from view, hidden until the next season uncovers them once more.

For additional images and more information about this discovery, see the coverage by the Associated Press.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.