Airborne laser scanning over the Karst Plateau, on the border between Slovenia and Italy, has revealed a network of prehistoric stone constructions unparalleled in Europe. Published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), the study identifies four dry-stone monumental megastructures that are the largest and most probably the oldest large-scale hunting system on the European continent.

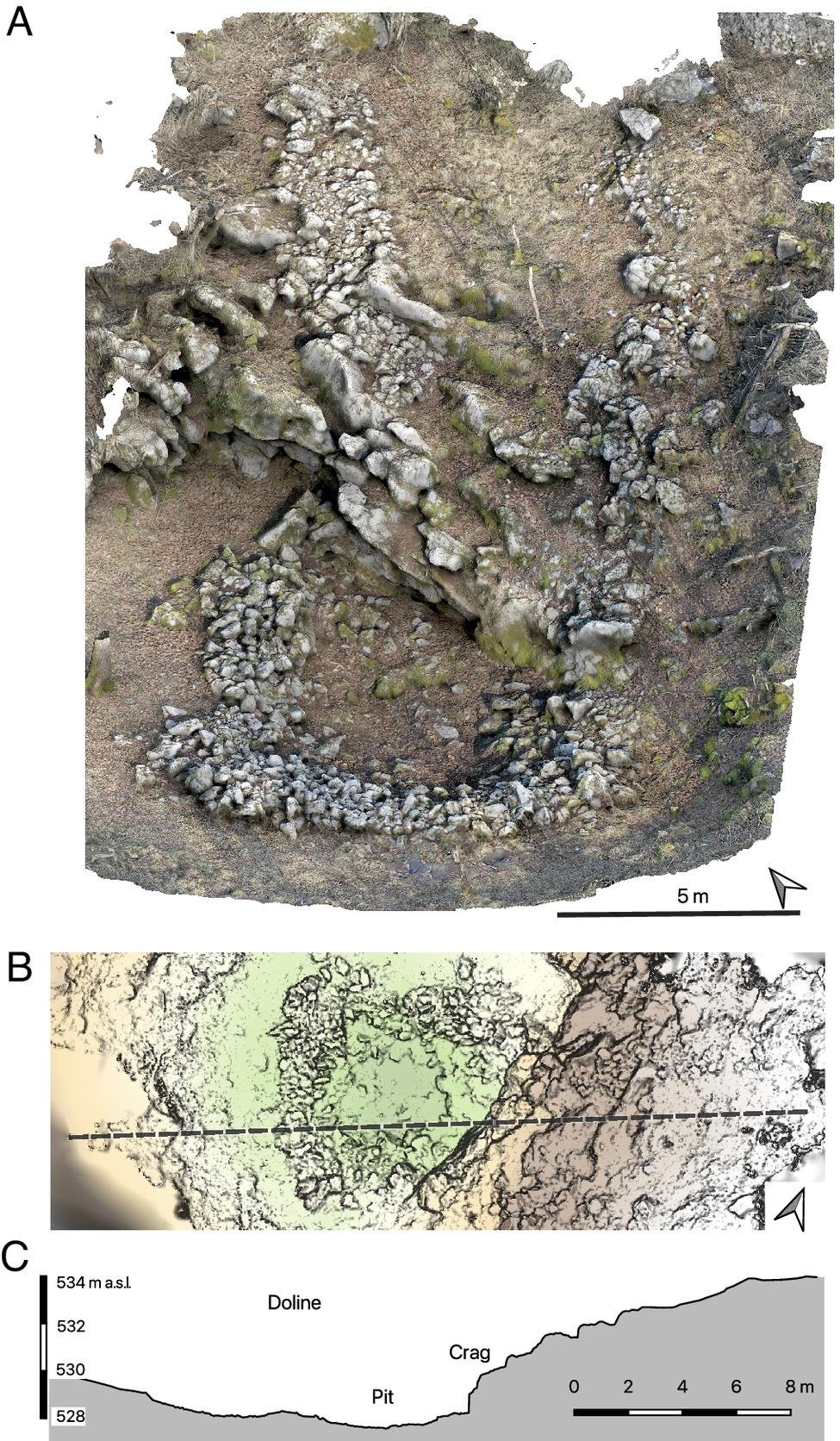

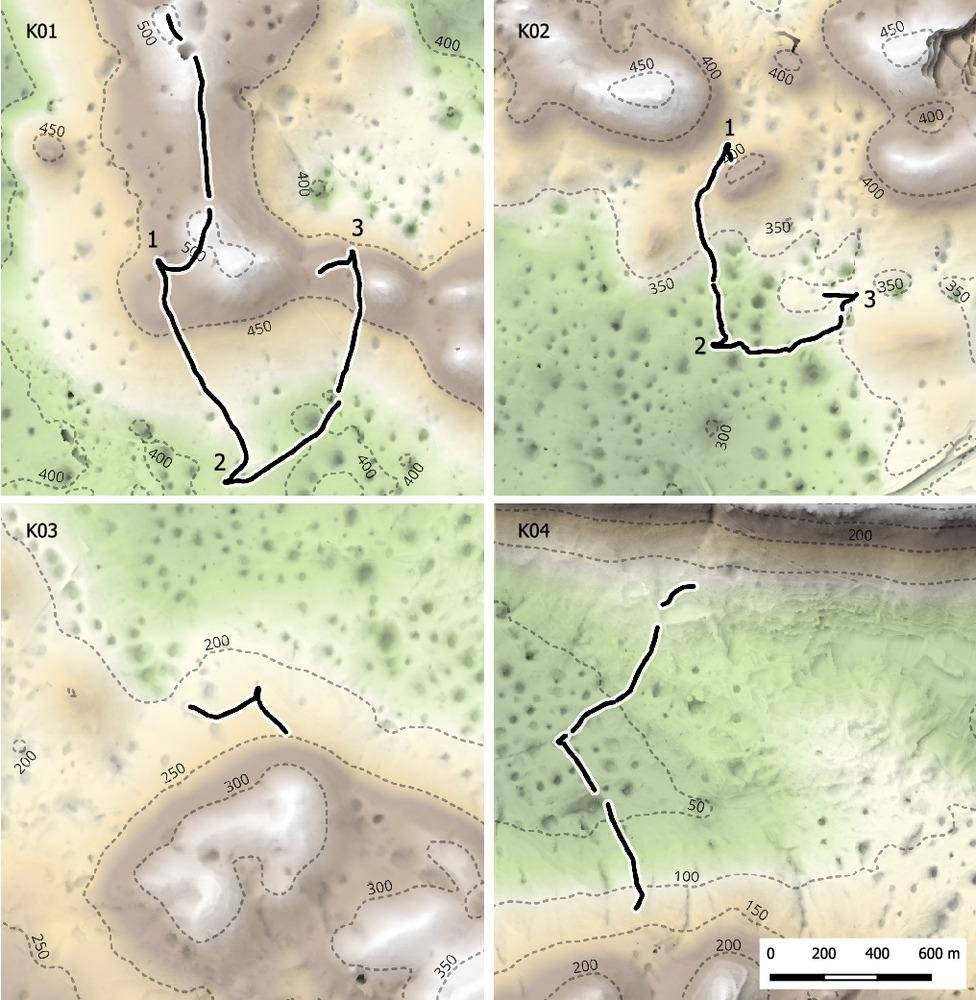

Researchers at the University of Ljubljana and the Institute for the Protection of Cultural Heritage of Slovenia surveyed around 870 square kilometers of hilly limestone terrain using airborne laser scanning (ALS). They identified four vast structures—labeled K01 through K04—each with extensive, low walls of stacked limestone ranging from 530 meters to over 3.5 kilometers in length. These alignments funnel into enclosed pits or natural depressions, which are typically hidden beneath cliffs or within sinkholes called dolines. On the ground, they form immense funnel-shaped layouts that appear to have directed herds of wild animals, such as red deer and other ungulates, into traps.

The discovery is the earliest known example of such large hunting installations in temperate Europe. They were built in a very similar manner to the “desert kites” of North Africa and Southwest Asia—vast stone traps used thousands of years ago to drive game animals across open landscapes. The Karst Plateau examples, however, were built in much greener, more temperate landscapes, demonstrating that similar communal hunting strategies also arose far from the deserts of the world.

Radiocarbon analysis of charcoal samples from one of the sites indicates that the structures were abandoned before the Late Bronze Age. Stratigraphic information suggests an even earlier origin, possibly in the Early or pre-Bronze Age, or even as far back as the Mesolithic era. When in use, the plateau would have been an open grassland where hunters could spot and guide herds across long distances. As forests gradually encroached on the region, the vast stone alignments were buried and forgotten.

The construction of such massive structures required top-level coordination, organization, and environmental understanding. The largest of the structures would have required approximately 5,000 person-hours of labor, pointing towards a cooperative effort well beyond that of small family groups. The positioning of the traps within the natural topography shows a high level of understanding of animal behavior and terrain, suggesting prehistoric communities had transformed their environments into purpose-built hunting systems.

Aside from their size and sophistication, these installations reveal a different dimension of European prehistory. They provide rare evidence that ancient communities coordinated large-scale collective labor, reshaping the landscape to manage wild animal populations before the advent of complex agricultural economies.

Whatever group of humans built them—late hunter-gatherers or early farmers—the Karst Plateau traps are a testament to human cooperation and adaptability. They blur the line between foraging and farming societies and challenge established notions about prehistoric Europe’s technological and social limits.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.

Nice article thank you