A Neanderthal skeleton, hidden deep in a limestone cave in southern Italy, has revealed a part of the human evolutionary story that scientists had long debated but had never directly observed.

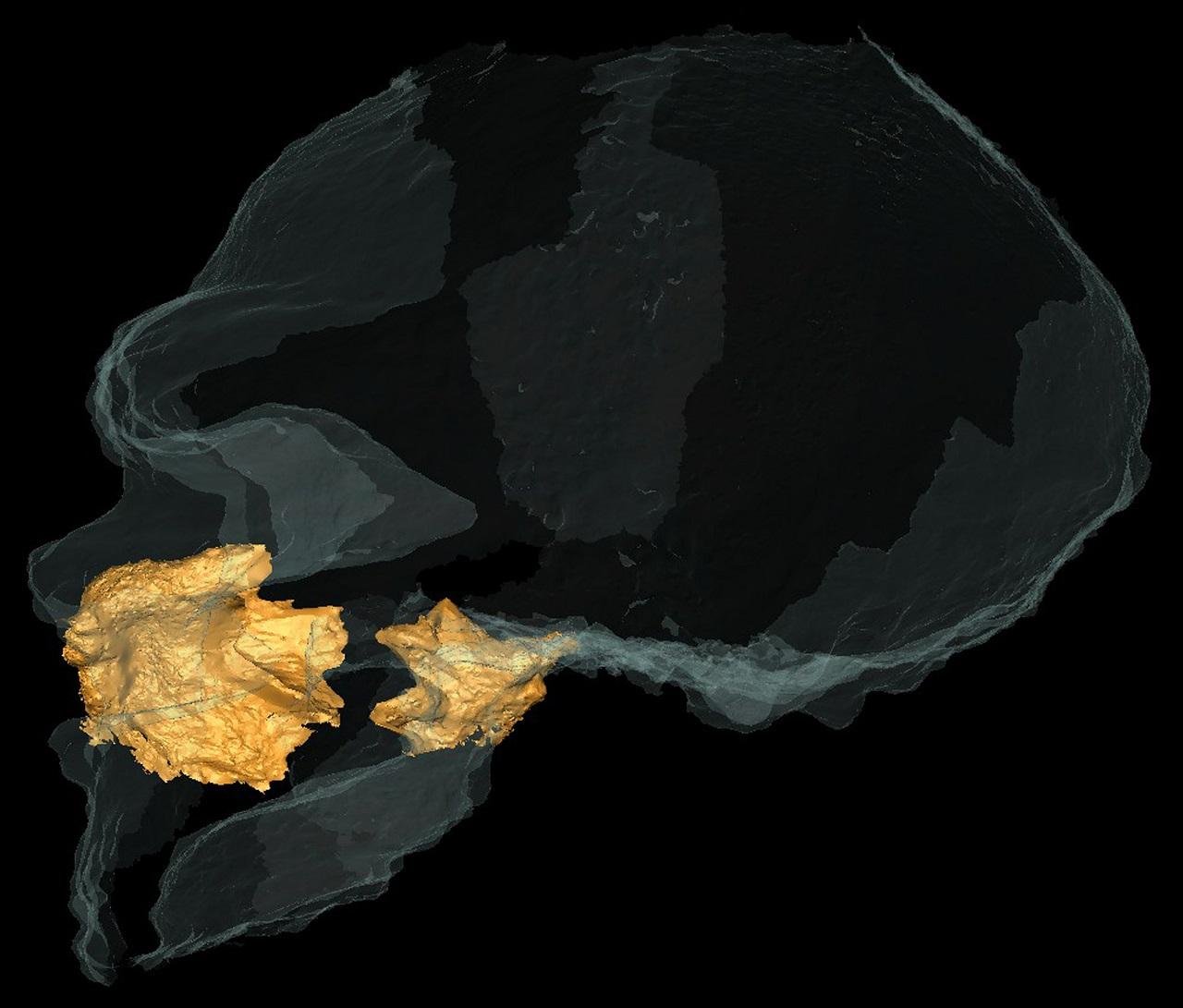

Using endoscopic tools to peer into the still-embedded remains of the Altamura individual, discovered in 1993 and dated to roughly 130,000 to 172,000 years ago, researchers have reconstructed the first complete internal view of a Neanderthal nasal cavity. Because these delicate bones are rarely preserved, the new find has allowed scientists to test long-standing assumptions about how Neanderthals adapted to the harsh climates of Ice Age Europe.

For decades, experts suspected that Neanderthals had special internal nasal features that would have aided in warming and humidifying cold air, compensating for the unusually large size of their nasal openings and prominent midfaces. These proposed traits, described as autapomorphies, included characteristic swellings along the nasal wall and the lack of bony structures above the lacrimal groove, but were purely theoretical because no fossil had ever preserved the internal nasal anatomy necessary to confirm these suppositions.

The Altamura specimen overturned that picture. When the researchers guided small cameras into the skull, they found no trace of the specialized structures thought to define Neanderthal noses. Instead, the inner cavity closely resembles that of modern humans, a finding that shows the hypothesized cold-climate adaptations simply did not exist. The team’s findings, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, effectively remove these features from the list of anatomical markers used to identify Neanderthal remains.

The findings reshape how scientists interpret Neanderthal facial evolution: the broad noses and prominent midfaces of Neanderthals have long been thought to be attributed to respiratory demands in extreme environments, but the new evidence suggests that the distinctive shape of the Neanderthal face emerged through a combination of evolutionary pressures rather than direct adaptation in the upper airways. Only the front part of the internal nasal cavity follows the outward projection of the midface, whereas the functional portions of the airway remain largely unchanged.

This find also helps resolve what had long been considered a paradox: Neanderthals shared many body proportions with modern human populations adapted to cold climates, while their wide nasal openings appeared better suited to warm, humid conditions. Researchers now argue that the Neanderthal nose worked efficiently for a large-bodied species living in cold environments, but via a configuration different from that seen in modern humans.

Beyond challenging old assumptions, the study opens new avenues for understanding Neanderthal biology. The detailed 3D digital model created from the endoscopic imaging will, for the first time, allow scientists to test how these ancient humans processed air, conserved heat, and met the energetic demands of life during the Late Pleistocene. More broadly, the extraordinary state of preservation at Altamura continues to transform the study of Neanderthal anatomy.

Comments 0