Archaeologists and Indigenous community members have unearthed evidence of an ancient ritual in Australia that has been continuously practiced for approximately 500 generations, spanning from the end of the last Ice Age to the 19th century. This remarkable find, discovered in Cloggs Cave in southeastern Australia, suggests the ritual may be the oldest known cultural practice still in existence.

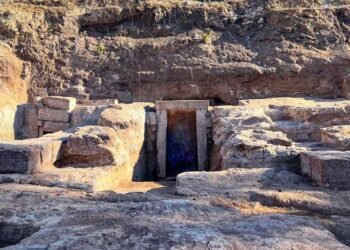

Between 2019 and 2020, a collaborative team consisting of archaeologists from Monash University and members of the GunaiKurnai Land and Waters Aboriginal Corporation (GLaWAC) conducted an excavation at Cloggs Cave, located near the Snowy River in Victoria. This site, partially excavated in the 1970s, revealed a profound and intricate record of Aboriginal culture spanning 25,000 years.

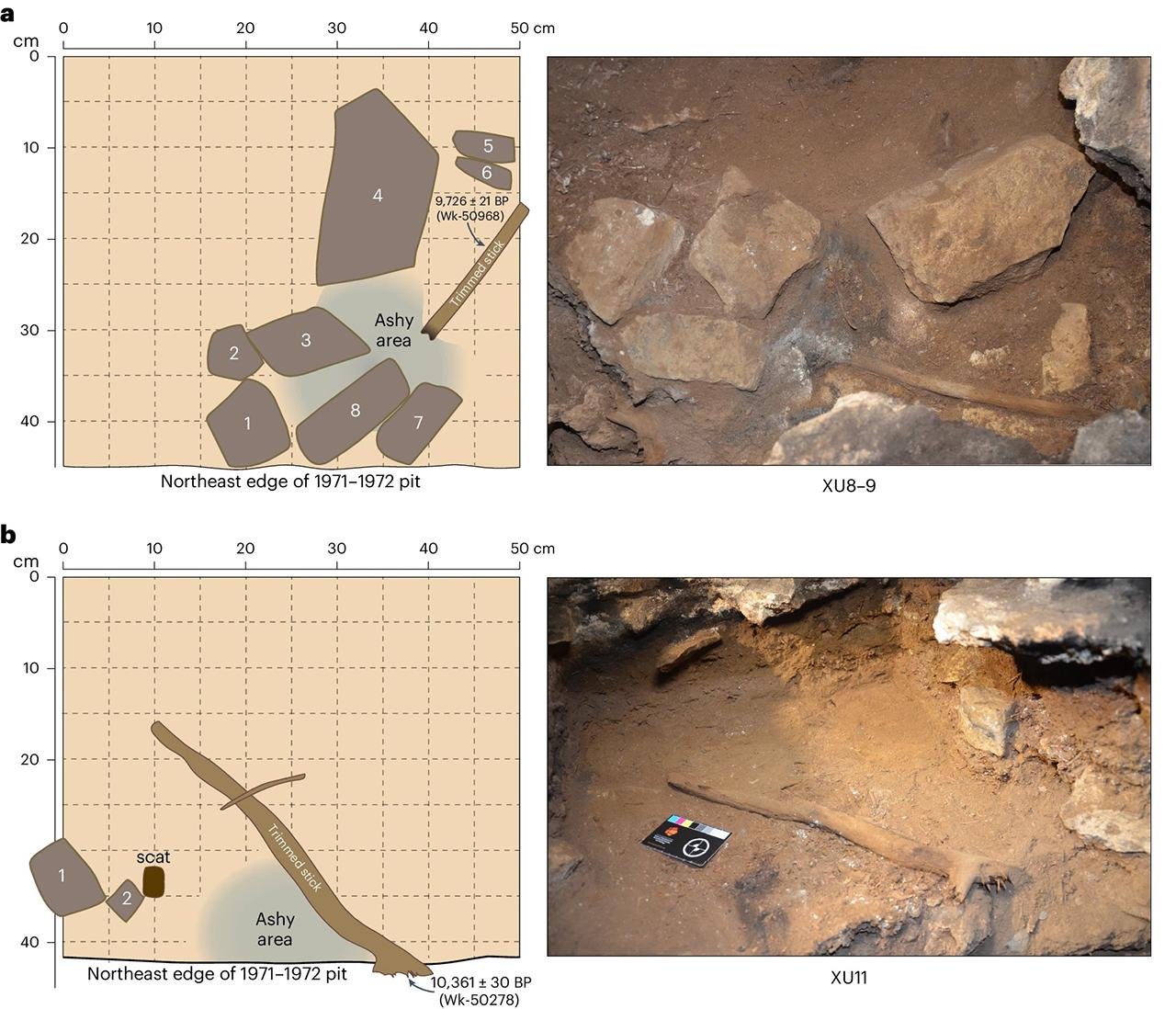

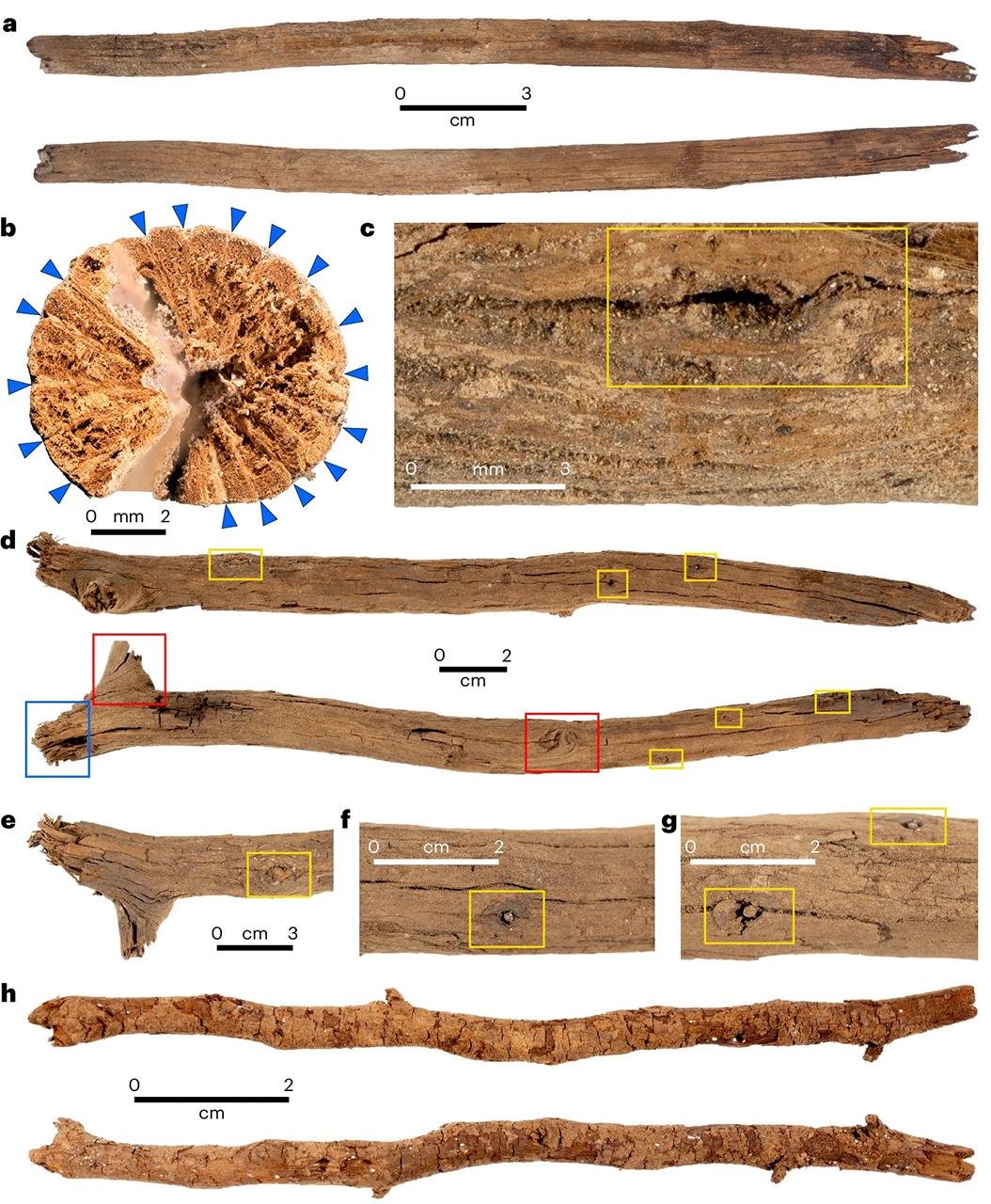

During the recent excavations, researchers discovered two miniature fireplaces, each containing a shaped stick made from the wood of the Casuarina tree. Radiocarbon dating of these artifacts revealed they were approximately 11,000 and 12,000 years old, making them the oldest known wooden artifacts in Australia.

The significance of the discovery was amplified when researchers connected it with 19th-century ethnographic accounts by Alfred Howitt, a pioneering anthropologist who documented the customs of tribes in southeastern Australia. Howitt described a ritual performed by the GunaiKurnai medicine men and women, known as “mulla-mullung.” This ritual involved smearing sticks with animal or human fat, placing them in a fire, and chanting the name of a target until the stick fell, thereby casting a spell.

The archaeological evidence found at Cloggs Cave closely matched Howitt’s descriptions. The sticks were made from Casuarina wood, smeared with fat, and slightly burned at the tips—an uncanny alignment with the ethnographic records.

The convergence of archaeological findings with ethnographic records underscores the enduring nature of Aboriginal traditions. “That’s 12,000 years of continuity, passing down knowledge from one generation to the next, of a cultural practice that has remained almost intact along 500 generations,” Bruno David, lead author of the study and an archaeologist at Monash University said. “That’s absolutely remarkable.”

This research was made possible through the partnership between archaeologists and the GunaiKurnai community. Russell Mullett, a GunaiKurnai elder and co-author of the study said: “It’s an opportunity to investigate our own people and what they have left for us to look at.” Mullett views the research as a means to reclaim cultural knowledge lost during the colonial era.

The findings at Cloggs Cave challenge the notion that societies without writing cannot preserve complex cultural practices over millennia. The preservation of these rituals, described in both archaeological and ethnographic records, showcases the resilience and continuity of Aboriginal culture.

The study also emphasizes the importance of integrating Indigenous knowledge with scientific methods. “For these artifacts to survive is just amazing. They’re telling us a story,” Mullett said. “A reminder that we are a living culture still connected to our ancient past. It’s only when you combine the Western scientific techniques with our traditional knowledge that the whole story can start to unfold.”

These findings were published in the journal Nature Human Behaviour.