Recent research has revealed that a mass ritual sacrifice of young children to a rain god in 15th-century Mexico coincided with a deadly drought in the region. The skeletal remains of at least 42 children, aged 2 to 7, were unearthed in 1980-1981 by archaeologists from the Templo Mayor Project (PTM), led by the Mexican National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH). Known as Offering 48, the discovery is located in the northwest section of the Templo Mayor, dedicated to Tlaloc. This monumental temple was a central hub of Mexica religious life.

During the IX Encuentro Libertar por el Saber conference titled Water and Life, archaeologist Leonardo López Luján, director of the Templo Mayor Project, presented new interpretations of this offering, supported by geological and isotopic analyses. “This was a ritual response to the catastrophic drought that devastated central Mexico between 1452 and 1454,” López Luján explained. The findings reveal how climatic adversity influenced both Mexica state policies and religious strategies.

The drought, which occurred during the reign of Moctezuma I (1440-1469), crippled agriculture and food supplies, leading to widespread famine. Historical records indicate that early summer droughts stunted crop growth, while autumn frosts destroyed maturing corn. These dual phenomena wreaked havoc on harvests, pushing the population to the brink of starvation. López Luján described the crisis as “a holocaust carried out to appease the fury of the gods.”

In response, the Mexica state initially opened royal granaries to redistribute food among its people. However, as resources dwindled, extreme measures were taken. Many families sold their children to neighboring regions, such as the Totonacs and Cohuixcas, in exchange for food. Meanwhile, religious authorities intensified rituals to appease Tlaloc and his divine attendants, the tlaloque, who were believed to control rainfall.

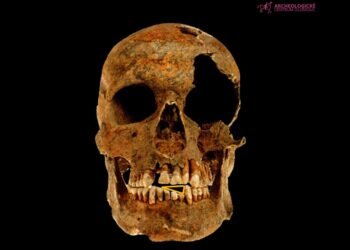

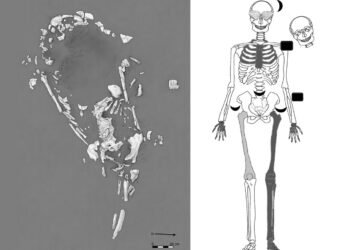

Offering 48 is a poignant example of these rituals. The children were carefully positioned in ashlar boxes on layers of marine sand, their bodies adorned with symbolic objects. Necklaces of chalchihuite stones, green beads in their mouths, and blue pigment—associated with Tlaloc—were used to anoint the remains. Surrounding the children were miniature jars, shells, bird bones, and 11 polychrome sculptures of Tlaloc’s face, crafted from volcanic tezontle stone.

These adornments likely aimed to personify the children as tlaloque, connecting them to the rain god’s divine entourage. Physical anthropologist Juan Alberto Román Berrelleza, who analyzed the remains, identified signs of porotic hyperostosis, a condition linked to malnutrition, reflecting the dire conditions faced by the population.

Isotopic studies by Dr. Diana Moreiras Reynaga of the University of British Columbia revealed that some sacrificed children originated from distant regions such as Oaxaca, Chiapas, and Guatemala. This highlights the extensive reach of Mexica rituals, which incorporated individuals from diverse areas into their religious practices.

Water and rainfall were deeply intertwined with Mexica religious and agricultural life. López Luján noted that nine of the 18 months in the Mexica calendar included ceremonies dedicated to ensuring rainfall. These events often culminated in sacrifices, reflecting the community’s reliance on supernatural intervention to sustain their society.

Despite these measures, the prolonged drought weakened the Mexica state, forcing mass migrations and increasing social strain. López Luján said that these sacrifices represented a combination of desperation and hope, as the community sought to reestablish harmony with their deities.

The discovery illustrates how ancient societies adapted to adversity through communal rituals and resource redistribution. López Luján remarked, “The Offering 48 discovery is a stark reminder of the lengths to which the Mexica went to ensure survival and stability in the face of environmental catastrophe.”